Dream Deferred

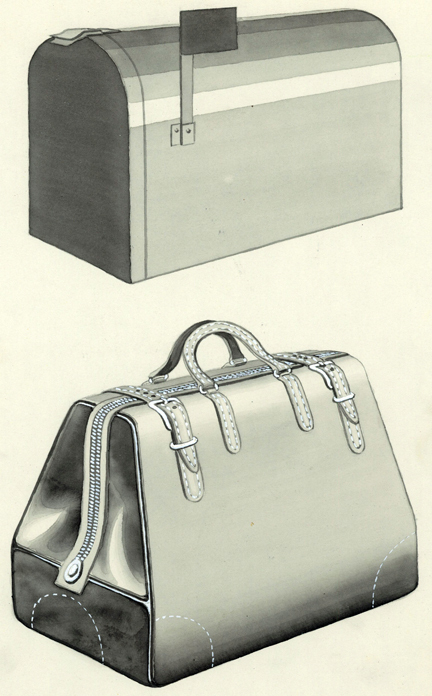

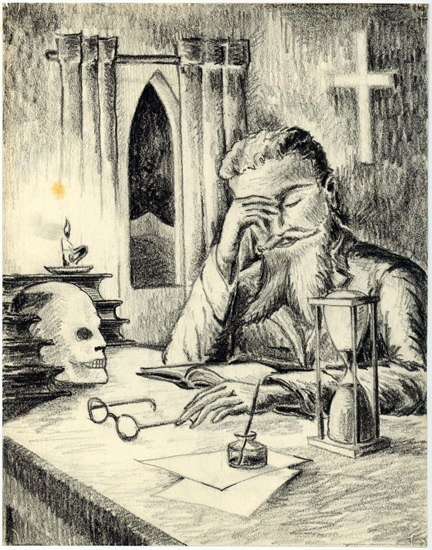

I have distinct memories of waking up in the middle of the night and walking out to the kitchen and seeing him from the back, hunched silently over an assignment at the kitchen table under the circular fluorescent ceiling light, drawing board tilted on the table, his pencils and brushes spread around him, the blue smoke of exhaled tobacco swirling in the air, completely unaware of my presence. As I grew older, my mother’s frequent rehashings of this chapter from their married life took on broader meaning and I became more aware of the narcissistically sadistic gratification with which she would conclude the tale, often in front of him; about how the long sleepless nights, the coffee and cigarettes eventually gave him a bleeding ulcer which put him in the hospital and forced him to quit the course. How he packed up all his assignment books, his finished and unfinished pieces with the notes and corrections from the instructors, put them neatly in a suitcase, put it in the attic and never looked at them again. How once again, part of a long litany of once agains, she was proved right and his poor choice, which caused such disruption and stress in their lives, had resulted in failure. Had he just listened to her in the first place this miserable ending could have been avoided. Years later as an adult, a professional, a husband, a parent, I couldn’t help but suspect that more than cigarettes, coffee and sleepless nights, it was her constant opposition and relentless nagging during this very critical and sincere quest that put him in the hospital and made him forsake a dream.

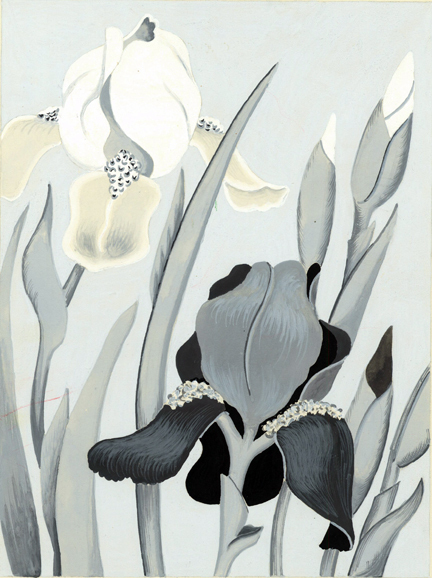

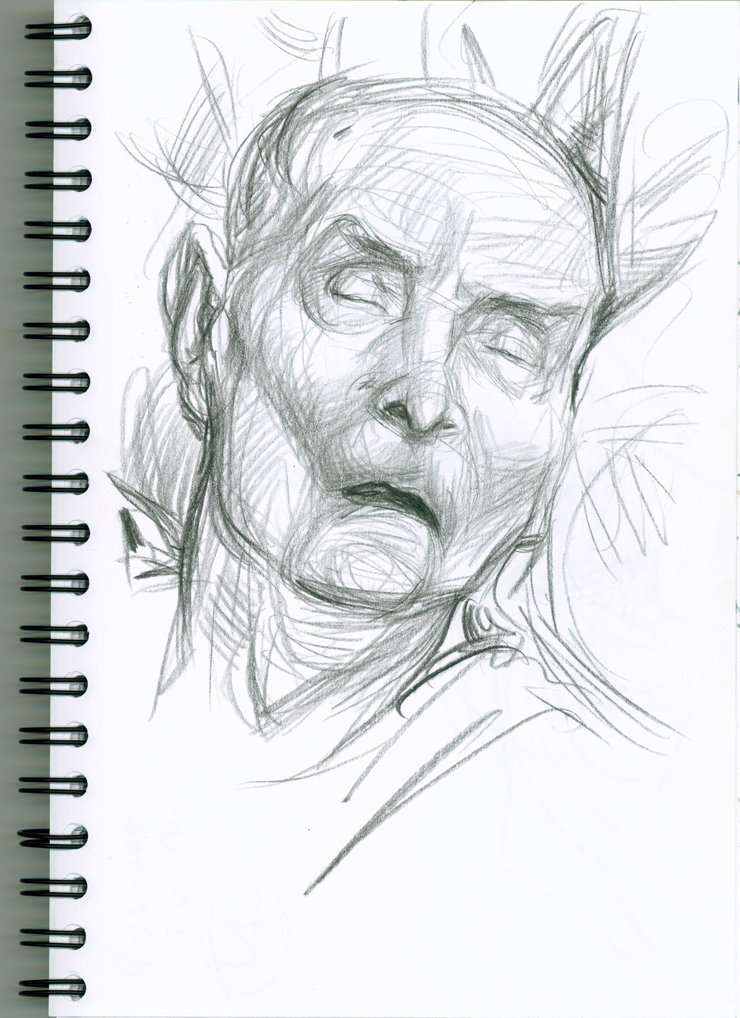

My father may have sequestered his suitcase full of assignments to the attic never to look at them again but as a kid I discovered it while doing some exploration in the darker recesses of that unfinished space in the house. I would often times go upstairs, pull the suitcase from the shadows, open it in the light coming through one of the small windows and look at all he did. I would devour the over 20 instructional books that made up the course, study his assignments, the commentary and corrections on overlays from his instructors, and compare their corrections to what he had done. It completely fascinated and awed me. There was something almost magical about this hidden world and in an unconscious way these repeated visits to his abandoned studies were planting the seeds of inspiration to a future decision about my own life. Neither one of us was aware of it at the time but a torch was being passed and I was to bring to fruition what he couldn’t.

On rare occasions over the course of a next decade or two he would pull out his pastels and render something from a photo or painting that appealed to him. During these projects he labored with a grim, burdened concentration. Never did he refer to the correspondence course or his crushed hopes of a career as a working artist. As if to add insult to injury my mother would find inspiration at these times to start a rendering of her own, just to show him how good she was.

The great scholar of mythologies, Joseph Campbell, talked of the tragedy of people not following their bliss. He tells a story of sitting in a restaurant overhearing an argument at the table next to him where the father is telling the child to drink his juice and the child refusing. The mother interjects and says to the father, “Don’t make him do what he doesn’t want to do.” The father responds, “If he does only what he wants to do, he’ll be dead. Look at me. I’ve never done a thing I’ve wanted to in my whole life.” My father was a very closed off person when he wasn’t in an impotent rage. He seemed to spend a great deal of his internal life in a very dark space. He came to life only when talking of his past, pre-1945, as a soccer player, a youthful mountain climber, a cross country skier and hiker who would disappear for weeks in the woods encountering blinding snow storms or gigantic stags. Of his times in the military, the brutality of training camp, the cruelty of his officers, the horror of endless waves of B-24s bombing his positions for hours on end driving many who were not killed to madness. Once, only once, late in his life when he was still willing to be present and connected, he told of watching the bombing of Dresden while on retreat; of how the incendiary bombs fell in such dense clusters that they collided in mid air and the entire sky seemed to rain fire on the city. I and my sons remember to this day the silence that fell among us at the dining room table.

His greatest joy, and the only way to see him genuinely laugh, was in telling stories about his high school years, the eccentric and usually harsh instructors, and of course the beatings that came from doing something wrong or mischievous in class. But that was all long ago. He never ever spoke in present time about his life or thoughts. Everything seemed to have ended around 1950. I used to think it was his inability to adjust to America that shut him down. I suspect, on further reflection and from connecting the many dots, that it was a series of crushed dreams, and a strangled sense of freedom and creativity that made him the dead, disengaged man we often saw in the house. A lifetime that consisted of doing what he thought was expected of him- being a husband, a father, working in a factory instead of behind a drawing table, never doing anything he really wanted to do.

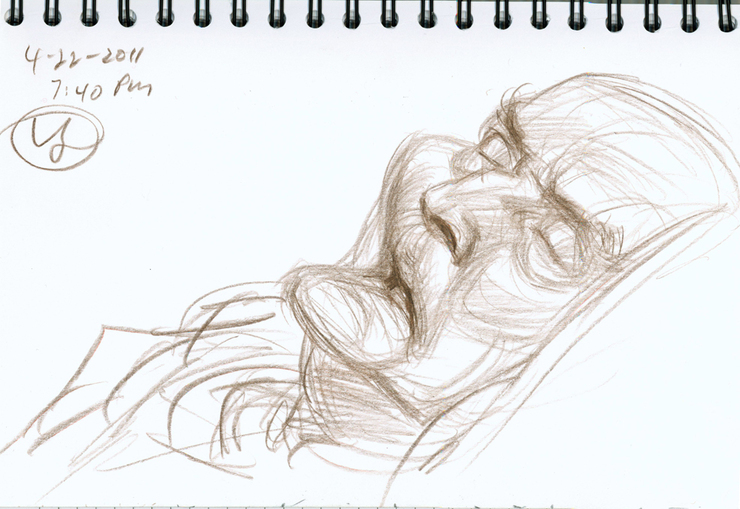

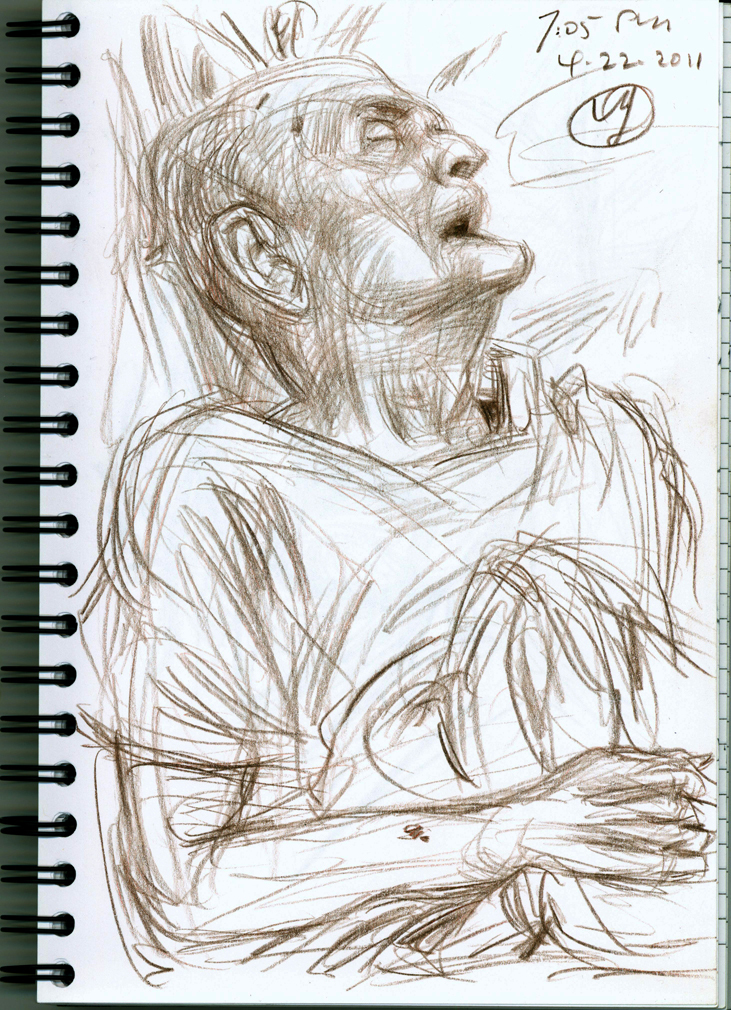

4-22-2011

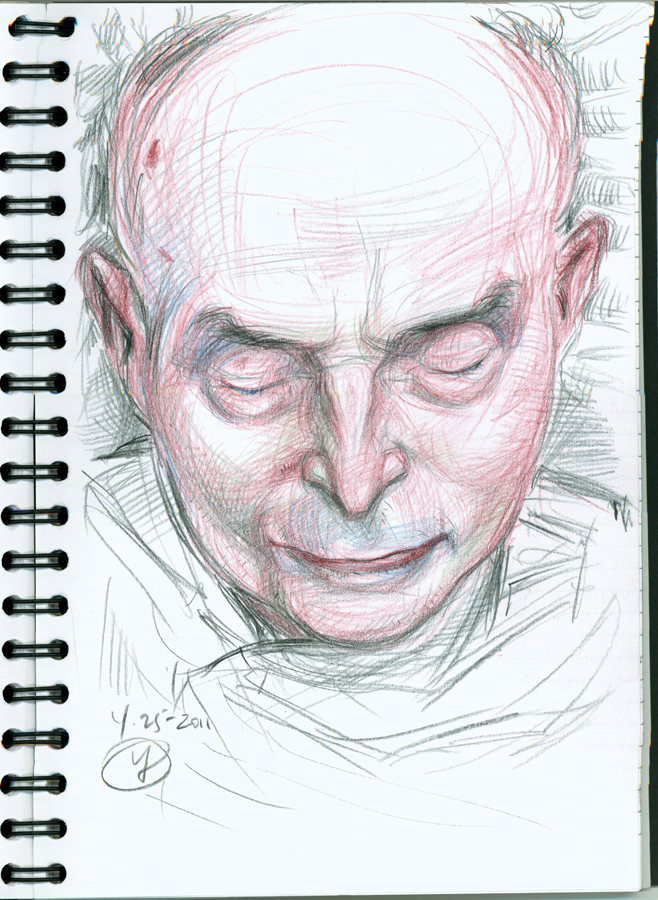

90 seconds. The time that had elapsed between my father dying and our arrival at the nursing home. The call had come late in the afternoon from the nurse to inform me that his condition had taken a turn for the worse, that he probably wasn’t expected to survive the weekend. He was in a very weak and wretched state just two nights before when I stopped by and responded neither to my conversation nor touch. I had been working in the garden and planned on seeing him later in the evening anyway, but responded to the nurse that I would be coming by as soon as I could. A deathbed vigil seemed a very likely scenario for the weekend.

A quick shower to clean off all the dirt, some clean clothes and Terri and I were off to the nursing facility. We were very low on gas and I stopped at the station to fill the tank. It’s impossible not to think that that time spent refueling was the critical time lost. I suppose it doesn’t matter. That it shouldn’t matter. When we arrived the aides were still holding his hands. He had acknowledged that he was aware of their presence by squeezing their hands on request before passing away. A final example of his selective deafness of the past decade. He was not in pain; he was technically not alone when he died. He had tears in his eyes at the moment of his death. Hearing that from the nurse more than anything else upset me because it took me off guard. Were they tears of joy or of fear? Were they tears of awe at some vision he was seeing? Were they tears of relief, surrender and deliverance? Were they tears of a great sadness and regret? God knows he was so sick and tired of his current condition, and of the humiliation of requiring assistance to manage his basic needs. Most certainly he longed to escape a life that had so thoroughly disappointed him, that had turned out nothing like he had probably hoped for as a young man. I thought for a brief moment that had I been there I could have deciphered a clue to the tears, but the uncomfortable truth was that the answer would have remained his locked within him.