Howard Brodie 1915-2010

My wife, Terri, and I were in California last week attending a workshop with Deepak Chopra in Carlsbad. She had some work to do in Los Angeles after the seminar and I was hoping to use a day to visit my old friend and mentor, Howard Brodie, with my son, Alex. My intuition was telling me this probably would be the last get together. As it happened, Howard passed away on the 12th, while we were still in Carlsbad. I was saddened, but also incredibly grateful for the friendship we shared since first meeting at the Hinckley Trial back in 1982. I have referred to Howard in my postings on my work for the USAF Art Program, marveling at his chops under severe combat situations and using his drawings as my benchmark. He will remain one of my benchmarks till my dying day.

We had visited Howard last year and I had written a tribute upon returning that I was intending to post on Drawger with some images of his work that Bruce, his son, was hoping to find time to send to me after he scanned them. I was only too aware of the task and responsibility Bruce had taking care of both his mom and dad who were both infirmed as well as the ranch they all lived on in San Miguel, California, and never thought of pressing the matter.

Back in 2001, when Howard was inducted into the Hall of Fame of the Society of Illustrators, I was asked to provide the essay accompanying his induction. It was a true and humbling honor. Applying necessary changes in tense and tweaking some parts that didn't read so tight, I include here the piece written for the event.

" I once wrote that Howard Brodie was the ultimate journalist. I still believe that." Walter Cronkite made no qualifications in a foreward he contributed for the book, DRAWING FIRE: The Combat Artist at War (Portola Press, 1996), a collection of Howard's writings and artwork spanning the decades from WWII to Vietnam. Mr. Cronkite, along with many of the "Greatest Generation", first became aware of the powerful artistry of Brodie's work during WWII via the Army weekly, YANK magazine. To a high school student like myself growing up in the latter part of the 60's kicking around the idea of making ART a career, my first exposure to his drawings, the equivalent of a punch to the creative head, and dare I say, heart, was by way of the CBS Evening News hosted by my favorite anchorman, Uncle Walter. It was an amazing era of notorious trials, the crazy and dangerous days of Sirhan Sirhan, Manson, My Lai, the Chicago Seven, Watergate. And there on the TV screen, regularly accompanying the always reliable reporting from the court, were Howard's on-the-spot drawings. In sharp contrast, however, to the vast majority of fellow courtroom artists, who, with all due respect, were competent but homogenous, Brodie's visual virtuosity made these incredible quantum leaps in substance and impact bringing a truly pulsating life and palpable dimension and insight to the personalities and events. I would be willing to bet plenty that many people turned specifically to the CBS Evening News not only to follow the progress of the trials but for the sheer pleasure of marveling at the energy and expressive vibrancy of these remarkable drawings.

Howard Brodie was born in Oakland, California, in 1915. With pride he listed his educational pedigree at Polytechnic High School in San Francisco, "alma mater to many famous athletes and statesmen", and then at the California School of Fine Arts, the oldest art school in the West. After a short stint at the SAN FRANCISCO EXAMINER, he found employment as a full-time sports illustrator with the SAN FRANCISCO CHRONICLE.

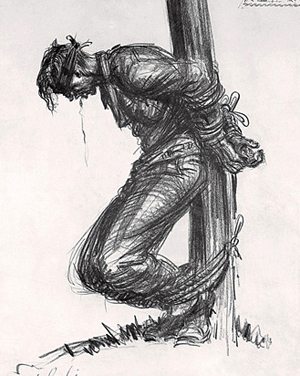

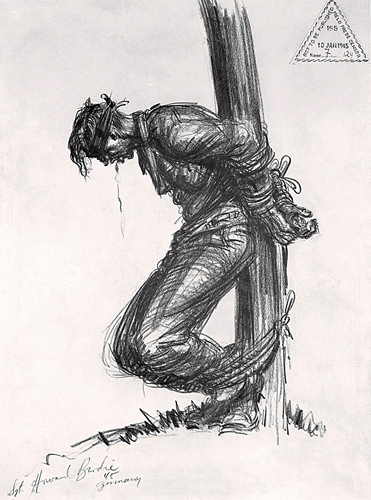

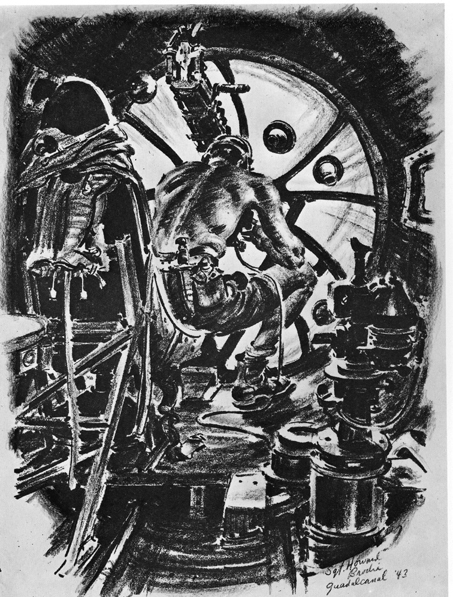

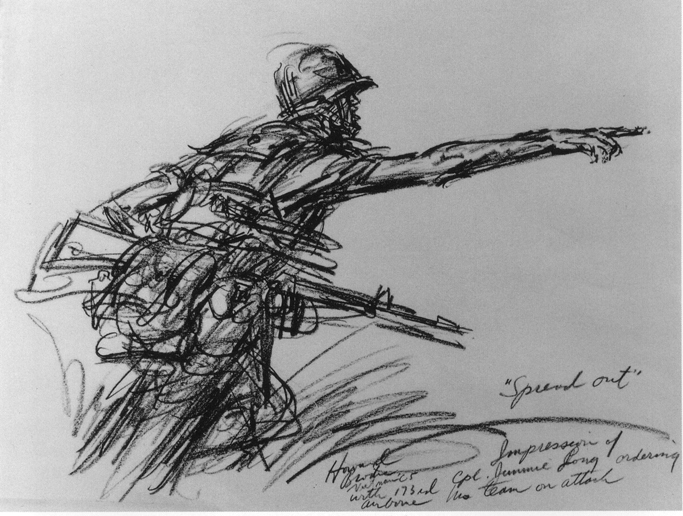

It was World War II that brought Howard to national attention. He enlisted in the Army and signed on as a combat artist for YANK Magazine, part of the "special forces" of soldiers (there were more than a hundred working for the military at the time) drawing the war from the enlisted man's point of view and becoming one of YANK's best known artists. With sketchpad, sharp eye, keen memory, and rock solid drawing chops, he began with covering the combat horrors of Guadacanal. Running out of his own supplies Brodie happened upon Prismacolor wax pencils used by the Navy for mapping purposes, and utilizing these simple tools produced beautiful, strong, brilliant, and unforgettable images, a masterful blend of muscular spontaneity and compassionate insight. No less a literary giant than James Jones, himself stationed in the same war zone, writes in the book, WWII, that the drawings Brodie produced from Guadacanal were a hit everywhere. He went on to visually record many of the major campaigns of the war in the Pacific and Europe including the Battle of the Bulge where he was awarded the Bronze Star for "aiding the wounded and coolness under fire".

After the Second World War, Brodie became a courtroom artist and consequently an invaluable eyewitness to many famous trials, some already mentioned. Though he worked for The Associated Press, CBS News, LIFE and COLLIER's he remained close to the military and returned as a combat artist to Korea, French Indochina, and Vietnam. He was philosophically level headed about killing in the heat of combat, but was a passionate advocate against the death penalty. The one drawing the Army censored during World War II happened at the Battle of the Bulge where he was the eyewitness artist at the execution of German soldiers who had infiltrated Allied lines posing as Gis. The drawing he produced, on the spot, of the dead German soldier transcended classifications of “enemy/friend” and instead served as an indictment against premeditated killing of any kind.

Throughout his career Howard produced drawings of specific events that came to represent more than just what was in the image. His drawing of Bobby Seale, strapped and gagged to his chair during the trial of the Chicago Seven, visually captured the tumult and chaos of the 60's in America.

Along with the already noted drawing of the executed German soldier there is the famous 'Moving Up' where three Gis on the march come to represent soldiers throughout time, exhausted yet relentlessly driven and grimly determined, an almost dispassionate will to survive etched in their faces. Brodie's confidence in his ability was obvious and his drawing skills awesome so that even when his line quality was at its wildest, most urgent, and expressionistic, the gestures never lost the sense of structure of his subject. We know the story in the image remains most important.

The story. The great jazz master Lester Young once referred to certain saxophonists as "all belly, no brain". Technical prowess, no matter how impressive, without a sense of love and artistic spirit ultimately adds up to little. Brodie's interest and quenchless curiosity in whomever or whatever was his subject came from a great, expansive love, a spiritual world view, that looked at mankind and embraced its contradictions and ironies and found value in the most horrid of circumstances. He once told me during a lunch break at the Hinckley trial, “I love all mankind- doesn’t mean I like them all, there are a lot I don’t like- but I love everyone.” A profound witness to much of this mad past century Howard recorded in both words and images the best and worst of what he'd seen and experienced. He remained a great, generous spirit till the end despite suffering a debilitating stroke (not surprisingly while drawing troops on maneuvers in the Mojave Desert in 1999) that while severely limiting his ability to draw, never diminished his passion for truth and beauty. His work is in the permanent collections of the Library of Congress, New Britain Museum of American Art, and the San Francisco Olympic Club. He was commissioned to draw on movie locations sketching the likes of Gregory Peck in PORK CHOP HILL, working with John Wayne in THE GREEN BERETS and Francis Ford Coppola in APOCALYPSE NOW. His visual knowledge of combat made him a go to person for film directors such as Terrence Malick on THE THIN RED LINE.

He was blessed with a long happy marriage to his artist-wife, Isabel, who survives him, and they were parents, both proud and close to, their son, Bruce, and daughter, Wendy, a well known chef. Few fathers could claim a son as devoted as Bruce and Howard’s final decade in large part was made immeasurably comfortable by Bruce’s tireless attention and love.

He was one of the heavy hitters at the San Francisco Academy of Art, but also held legendary intensive drawing seminars at his ranch in Central California until his stroke.

Brodie was inducted into the Society of Illustrators Hall of Fame in 2001. With Howard’s passing, we lose one of the last links to a golden period of illustration- where artists truly had serious drawing chops that would shame many of us. But it was his philosophy that transcended even his enormous abilities; “Love is the heart of Life and Art.”

This is the setup.

It’s 1982. The courthouse is packed and confusing. The security (at least by 1982 standards) is tense and tight and tediously slow moving. Lots of bag inspection and ID double checking. My belly and bladder, grumbling and acting out the nervousness I feel standing in line, keep my eyes darting around for the nearest ‘MEN’S ROOM’ sign. Presumed proper press credentials from THE WASHINGTON POST are in my possession, along with a burdensome load of 18”x 24” drawing pads, pencils, charcoals, pens, erasers, pencil sharpeners, you name it- everything but confidence.

Feeling like such an amateur, so unprepared, even with the imposing and clumsy arsenal of drawing materials. But it IS the first day of the trial of John Hinckley for the attempted assassination of then President Ronald Reagan. Maybe I do have a right to feel the butterflies. I’d done courtroom work before, for ABC-TV in New York City, sometimes under the craziest of circumstances, like the mad, moment’s notice, crack of dawn rush to the arraignment of Son of Sam in Brooklyn from the loft I was living in Manhattan at the time. But this feels like real serious business here in Washington, D.C..

Then the floor drops out from beneath me. My press credentials are missing a crucial signature/confirmation from someone at the POST. I am taken out of line, and as the reporter I’m assigned with is scrambling to get the necessary assistance and clearance from back at headquarters, I watch as the crowd files past me into the courtroom. I’m aware of other people who definitely look like courtroom artists, but it’s all turning into a blur as it becomes clear that my early arrival and good positioning in the line was worth nothing and if I’m lucky I’ll be able to get in sometime during the day, once everyone else has settled in. Nothing like the prospect of climbing over heads during a procedure.

It felt like a month, but in actuality, calls were made quickly, the missing credentials were secured and in the middle of the continuing blur I find myself working my way through the crowded courtroom with just seconds to spare before the trial starts. I am directed to where the courtroom artists are seated- and the rows are all filled. There is so much perspiration running down my back, I might as well be swimming. Somehow, somehow, I am able to wedge myself in the second row between already set up sketch artists and try my best NOT to be obvious. My pads are literally on the laps of the artists sitting on both sides of me. My bag filled with charcoals and pencils is stuffed between my legs and I can hardly move. A headachy sense of lightness from nervous dehydration has set in and the entire setup is looking terribly overwhelming. Nothing like starting your first day with a near complete fuck-up. The other artists have already been scribbling away, some with entire courtroom settings set down as referential starting points. Briefly, I try to compose myself, take a deep breath, get my bearings, and, considering my cramped conditions, jot down some visual notes on the pad bent on my lap.

In a little while it becomes clear to me that I’m off my mark, I’m not in the game yet. Intuition tells me to just lay back and try to take in the scene, just get a gander at what everyone else is doing. Looking around, I recognize styles seen on the TV screen and begin connecting them to the faces. Everyone is looking very intently at what’s happening ahead. Remarkable how many of the sketch artists are women. I’m calming down a bit. My self-confidence is starting to reappear. Some of the drawings around me look pretty weak, and I know that once I’m rolling I’ll kick ass. At the very least, do better work than what I’m seeing to my left and right.

Aside from myself, there’s only one other male in the courtroom artist grouping. A bald guy in the row ahead. Dressed all in black. White mustache. I lean ahead to get a better view. What’s he doing? Where are all his art supplies? I came loaded for bear. Where are the million and one colored chalks, and brushes, and pens? He’s got his drawing pad open, 18”x24”, like me. That’s cool. But all he’s got are some Prismacolor pencils- three colors- Tuscan Red, Black, and a dark blue. My attention is drawn to his lightning fast gestural marks setting his characters in place. With Zen-like jottings and jabs, he establishes the basic structure in black pencil and then brings in the red and blue to fill in and add weight. The energy is startling and the confidence is unmistakable. Bells ring in my head and the visual connection yells from the back of my brain- “Holy Shit. This is Howard Brodie!” I flashed back to my high school days, and earlier; to my first exposure to his drawings on CBS-TV, anchored by Uncle Walter Cronkite, the most trusted man in America. Notorious trials. Sirhan Sirhan, The Chicago Seven, Lt. Calley, Manson. On network TV, Howard’s style and jaw dropping virtuosity stood far out in front of the work of most other courtroom artists. They pulsated and jumped. The gestures and line quality were positively kinetic, possessing a life force all their own while simultaneously zeroing in with laser sharp insight to describe personality and depth of character. Nearly every other courtroom artist on the tube looked amateurish or ham fisted. I wasn’t entirely sure back then what I was going to be doing with my life, but if I ever did this kind of work I wanted to be this good. Brodie carried a serious axe. He was the benchmark. He was an artist I wanted to emulate. Shit, he was sitting in front of me.

For a while I maintained my forward lean and watched Howard, transfixed by the deliberate, considered, but near lightning quick gestures populating the sheet of paper; these abstract expressionist squiggles, streaks and dashes pulling together in short time to create faces with real palpable expressions and bodies that could have gotten up and walked off the pad. And all with just three colored pencils! There was a glitch in the proceedings and a recess was announced. Bodies relaxed, people stood up. I finally got a chance to move my arms out of my boxed in position. Howard continued filling in the details sealed in his mind’s eye on the sheet of paper, untroubled by the break. I leaned further and over the bench.

“Excuse me.” Hedging my bets here, because as much as I felt confident this was Brodie from the drawing in front of me, I wasn’t willing to look like an idiot.

He turned and looked at me. “Yes.”

“Are you Howard Brodie?”

“Why yes I am.”

I relaxed inside, and reached out my hand to shake his. “ My name is Victor Juhasz. What a pleasure to meet you. Howard, you are one of my fucking heroes.”

He didn’t miss a beat.

“Glad to fucking meet you, Victor.”