The Prodigal Son Returns- Part 2- On the Bataan with the 24MEU

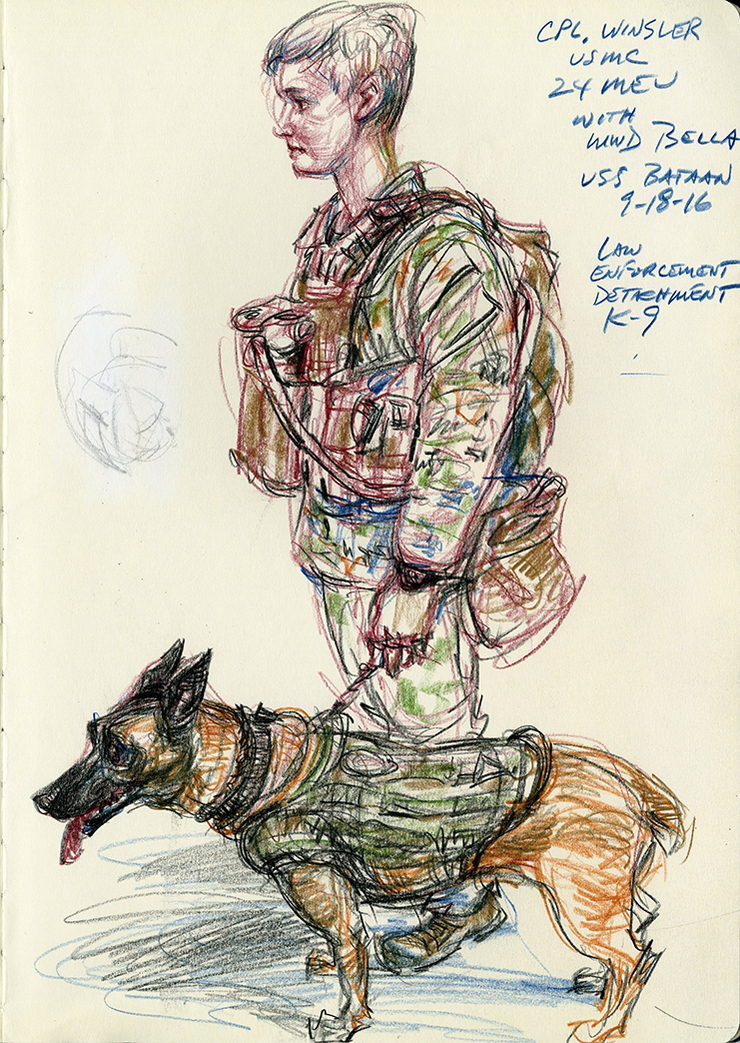

Fast forward a couple years. Colonel Streeter has maintained contact with us even as his assignments and responsibilities have changed. He’s still intent on adding artwork to the current historical record and an integral part of the Marine Corps once again. In the summer of 2016 I receive an email asking if I would like to do a short embed with the 24th MEU (Marine Expeditionary Unit) based in Camp Lejeune and draw training exercises aboard the LHD-5 USS Bataan. He had been in contact with his friend and fellow colonel, Ryan “Chick” Rideout, commanding officer of the 24th, who expressed great interest in bringing some artists along. Captain Eric Pfister, commanding officer of the Bataan also gave an enthusiastic thumbs up.

It’s been a long time since civilians have been invited. For decades the only artists were official Marine combat artists. There is some logic behind this. A Marine combat artist is expected to not only draw but pick up a weapon if necessary. The Marines are the shock and awe force in the military. (Some clarification is worth noting here. Combat artist is a title designated to someone in uniform also performing duty as an artist in the field. War artist identifies a civilian.) Once again, Richard Johnson and I- the civilians- along with Colonel Streeter and former Marine combat artists Mike Fay and Kristopher Battles, were going to do some drawing on the high seas.

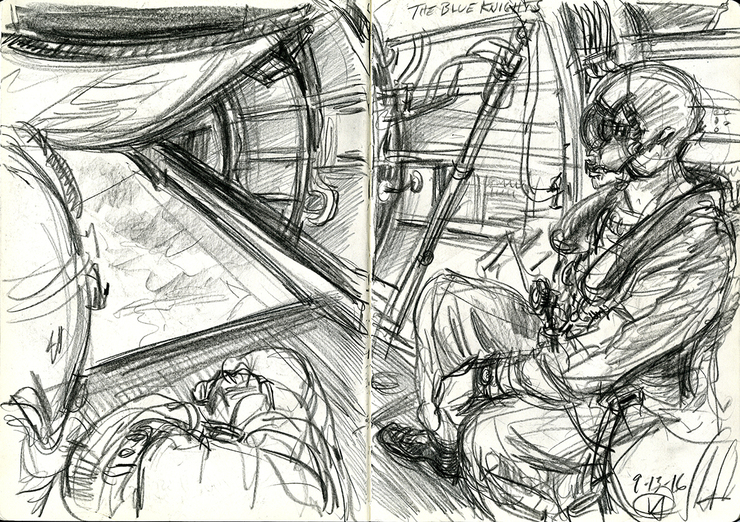

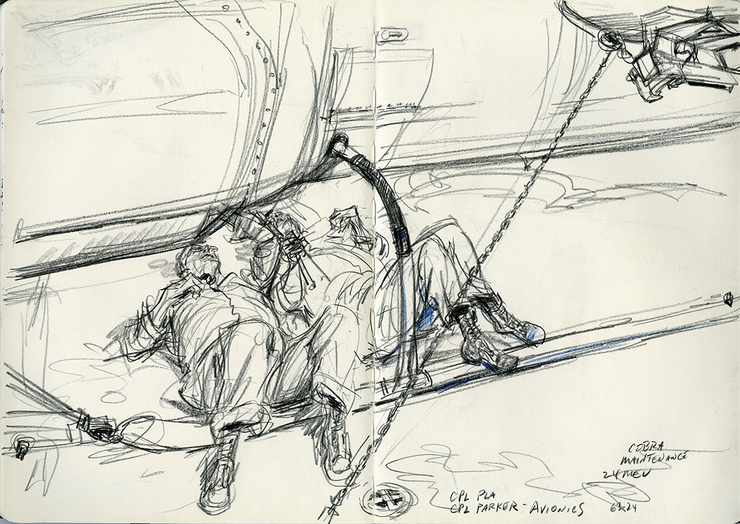

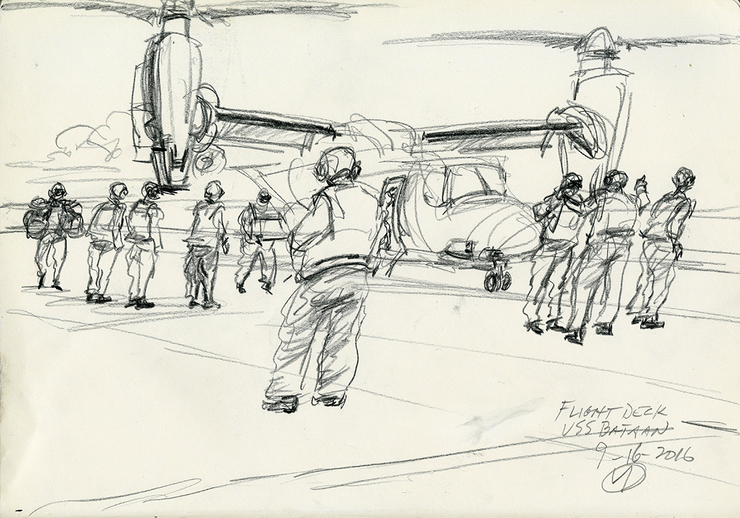

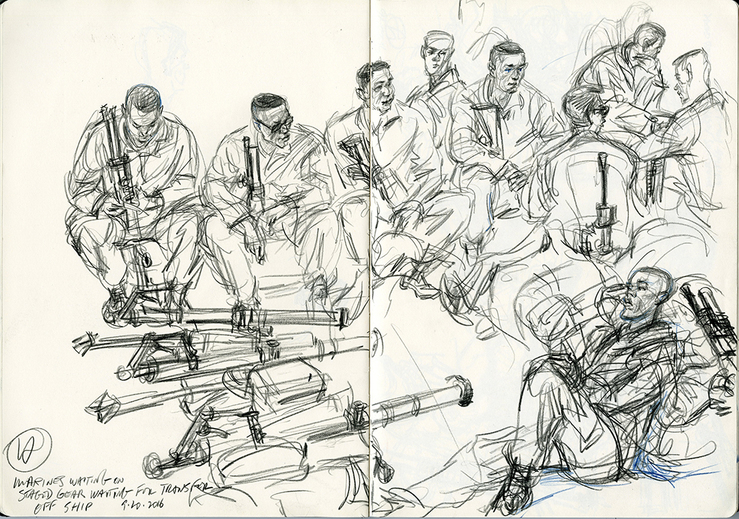

Because of our different schedules Kris, Mike and Richard managed to board the Bataan a couple days ahead of Colonel Streeter and myself. Colonel Streeter and I accompanied Colonel Rideout and team via air transport on the V-22 Osprey, that crazy helicopter that can convert to a plane. It’s a beast. Our crew were members of the Blue Knights. Once again I made a fool of myself trying to successfully strap in among the Marines. I’ve been there before. I’ll master all the clipping and buckling while mashed in between soldiers or Marines only to forget the procedure by the next time an opportunity pops up to fly. Rucksacks, weaponry, art supplies, backpacks piled high with jigsaw puzzle precision. Luckily I held onto one sketchbook and some pencils packed in vest pockets that weren’t snapping from all the compression and did a couple drawings during the bumpy ride in the sky. We were originally supposed to land on the Bataan somewhere in the Atlantic but mechanical problems kept the LHD in port. We landed and were driven to the boat which we then boarded. By the next day the mechanical issues were resolved and we left port.

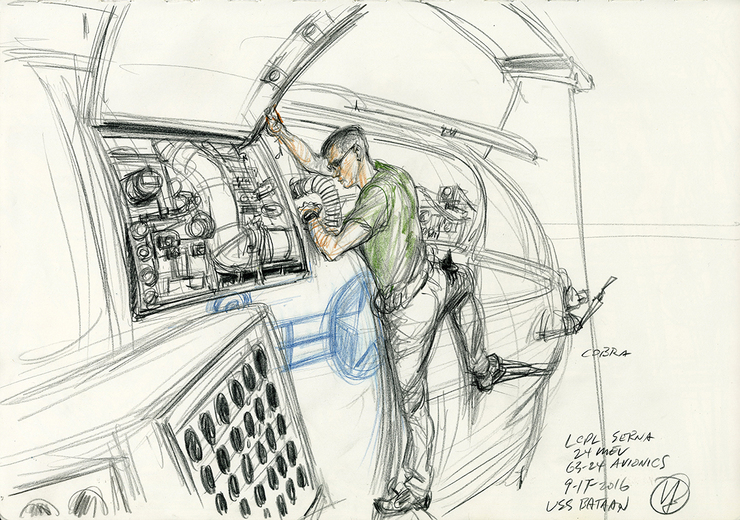

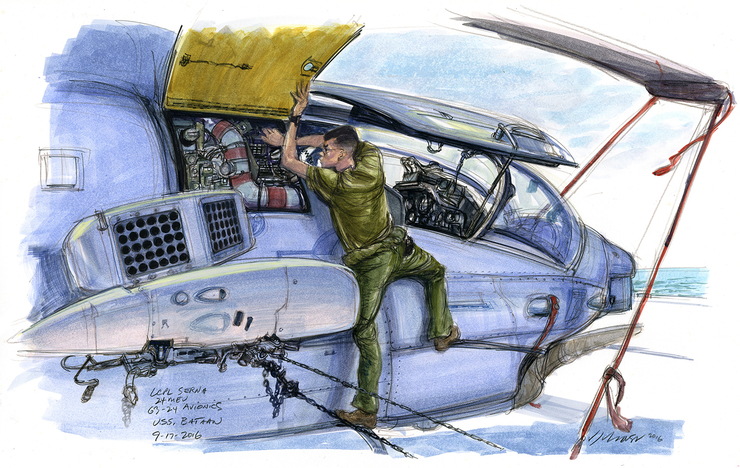

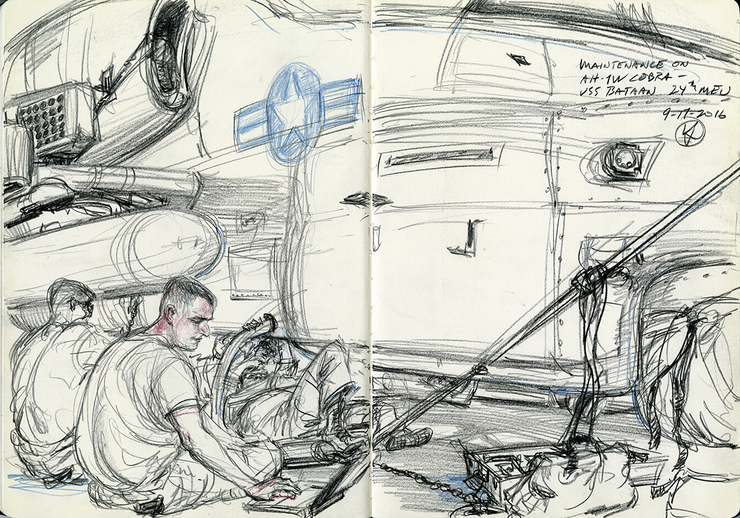

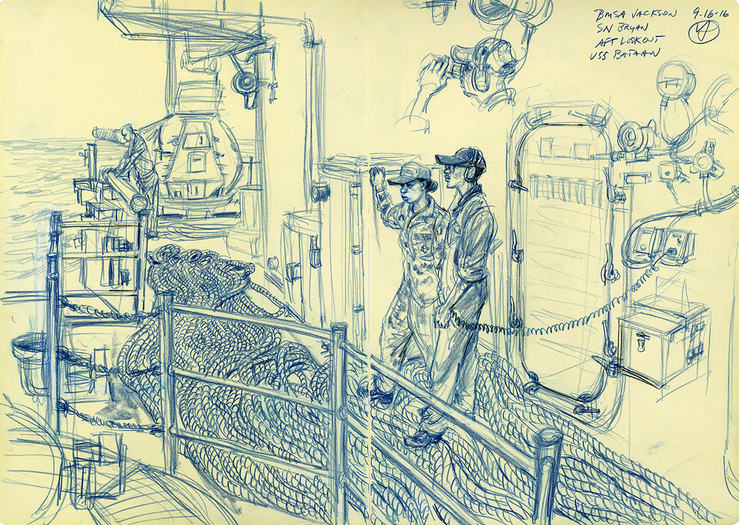

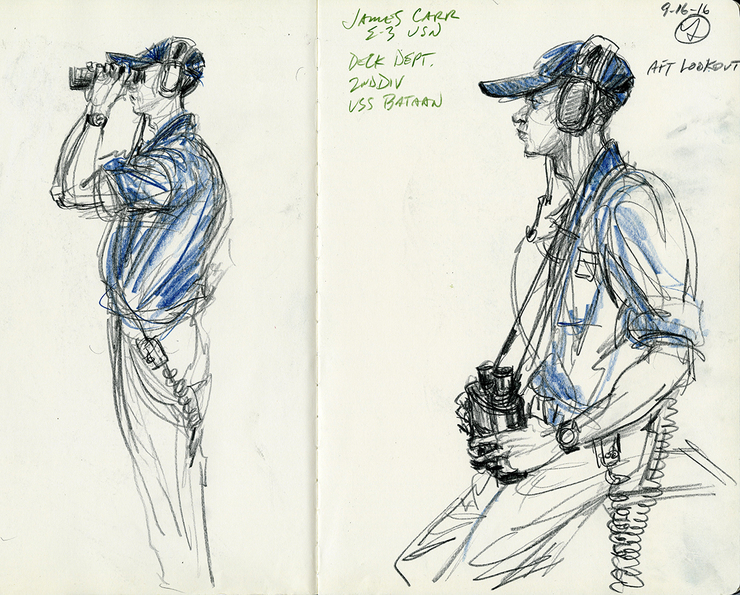

If there is one thing I’ve learned, at least from what I’ve observed in the Corps, is that Colonels rule. They seem to be the most proactive rank, who get the respect and whose directives are not questioned. Apparently, the fact that we received the blessings of the Colonels, along with the Captain and his team, allowed us artists generous access to all but the most sensitive locations on the ship. That in turn allowed us to concentrate on what we were doing without concern that we’d be getting shuttled to another situation. It also allowed us to pursue our own objectives. We were spread out across the ship. Occasionally, we’d share a drawing experience. It made for interesting perspectives on the same subjects.

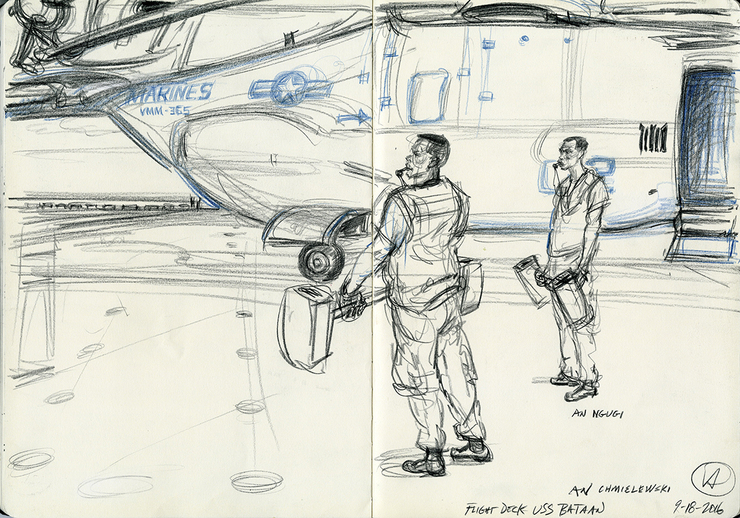

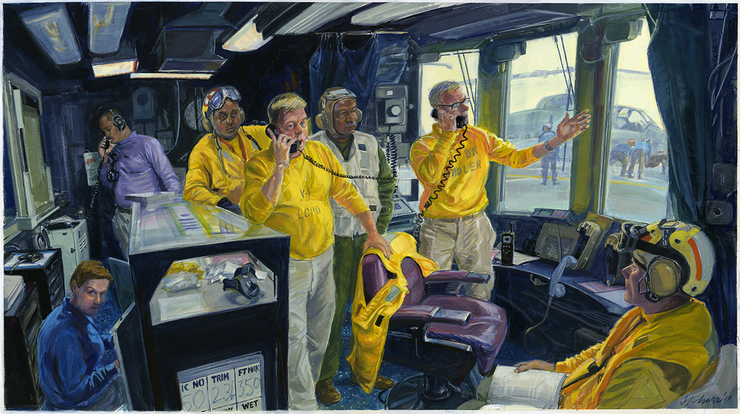

The teams, from the flight deck room and the flight deck to the Captain’s tower couldn’t have been more accommodating, and considering the crowded or hectic circumstances at any number of times, that’s saying a lot. All we had to do was follow the protocols about wearing proper protective gear, especially if on the flight deck during operations, and make sure that we didn’t drop anything on the flight deck. It’s quite a remarkable fact that the tiniest bit of debris on the flight deck can get sucked into a jet engine and destroy at multimillion dollar machine. Every day Marines and sailors, shoulder to shoulder, from one end of the flight deck to the other, conducted the ‘walk-down’ searching for FOD, potential foreign object damage, prior to landings or take-off operations.

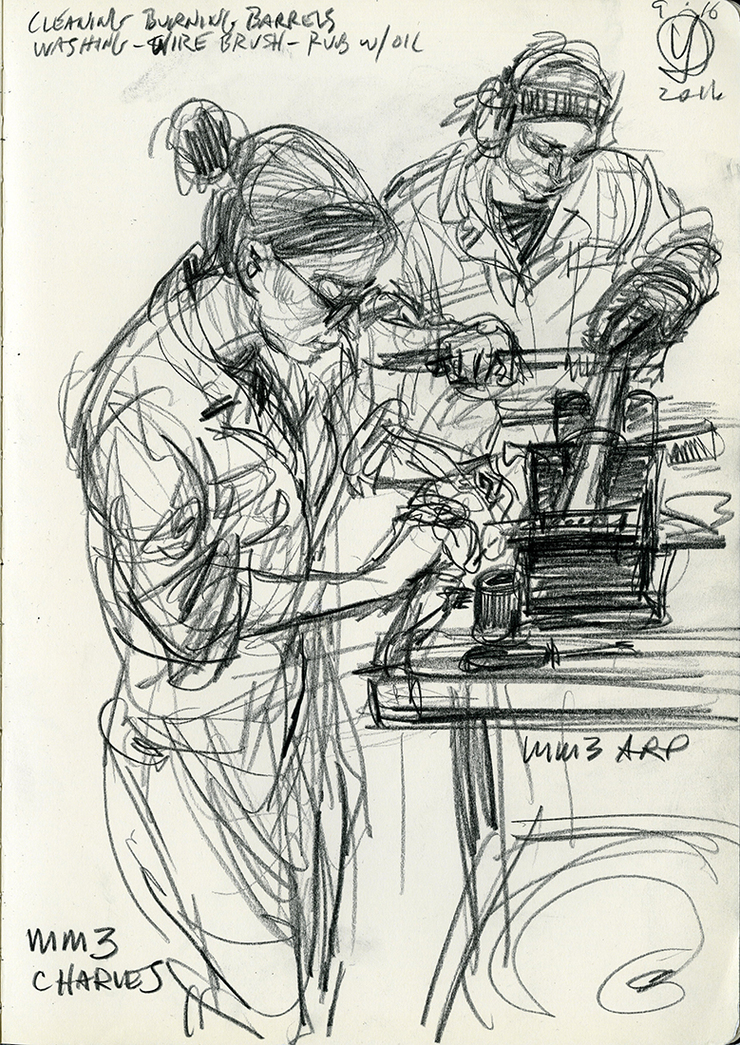

We found ourselves invited by various teams to observe and draw their work. The personnel managing the engines were particularly pleased to have us there. It’s a brutal and unsexy existence in that punishing heat but someone has to keep the ship operating. Uniforms hung limply on bodies that appeared to have burned off any excess weight. Those of us attempting to sketch down in the bowels soon found that our uncontrollable sweat, pouring in almost cartoonish amounts, was soaking the paper and making it nearly impossible to draw. I made a note to myself to take another stab at it should I get a chance to return.

I was on the Bataan for 8 days. I didn’t even begin to get myself oriented to the maze of winding passageways and steps intersecting with the various levels till maybe day 6. It would almost be comical except for the man overboard drills that periodically took place which required us to return to our team assembly spaces from wherever we were on this enormous ship in just a few minutes. Not fun, especially if you were on deck with ear guards and unaware that the alarm was being issued over the loudspeakers. I made another mental note to bring a Go-Pro cam on the next such mission and record the various journeys.

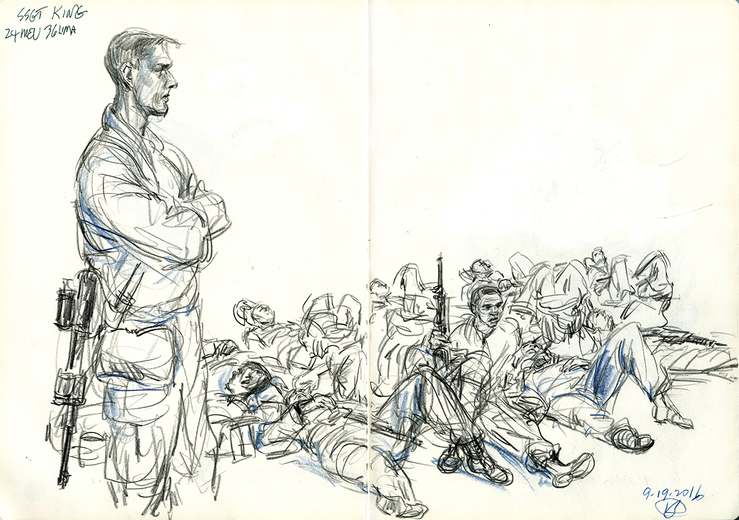

Our berths were in the officer’s section which meant we slept in slightly less crowded quarters- four to a room- than the grunts in the lower levels who were managing like sardines. Colonel Streeter has his own room, naturally. Eating times were relatively short, considering the number of personnel on board, and strictly enforced. If you arrived late and without a really good reason you just skipped your meal. That said, the wardroom- the dining room-always had some fruit or power bar to grab if necessary.

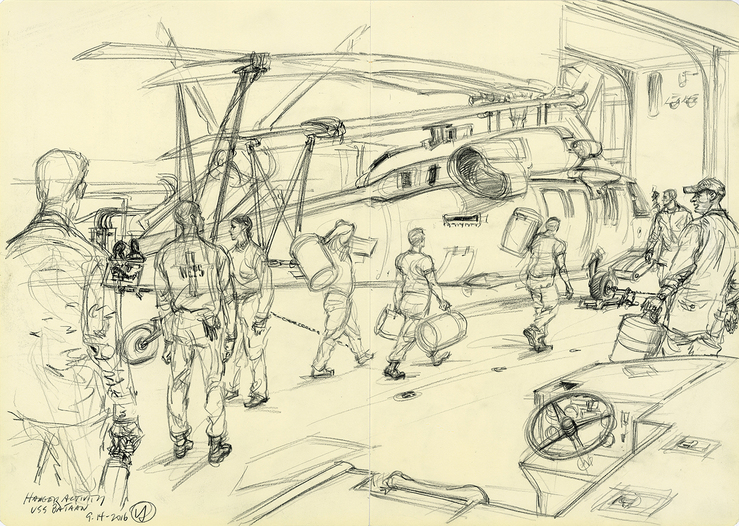

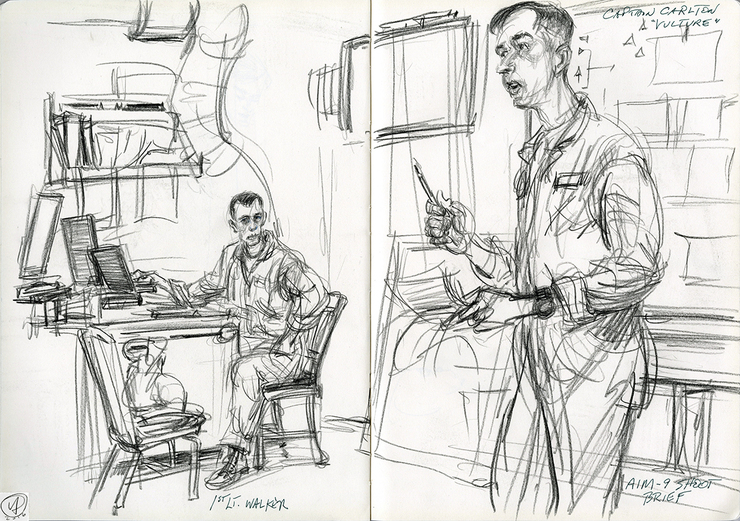

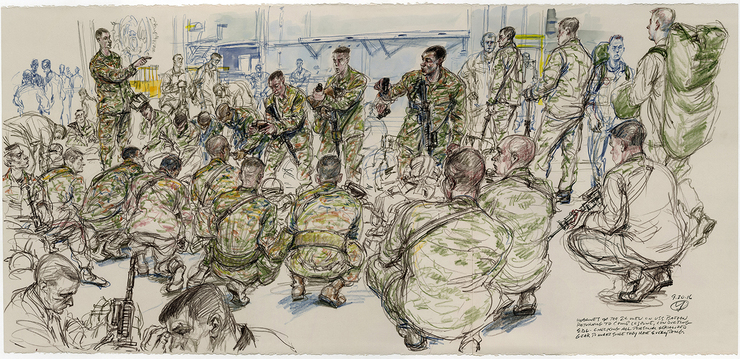

One thing that caught my attention was the enormous amount of time the Marine officers spent huddled together going over instructions, details, procedures and protocols when not with their grunts. If I was making a late night visit to the wardroom they would be in there comparing notes and prepping for the next day’s drills. If I was passing through the hanger there would be a group. I didn’t sleep all that much on the mission and wondered when, if ever, they found a couple hours. Ah, youth.

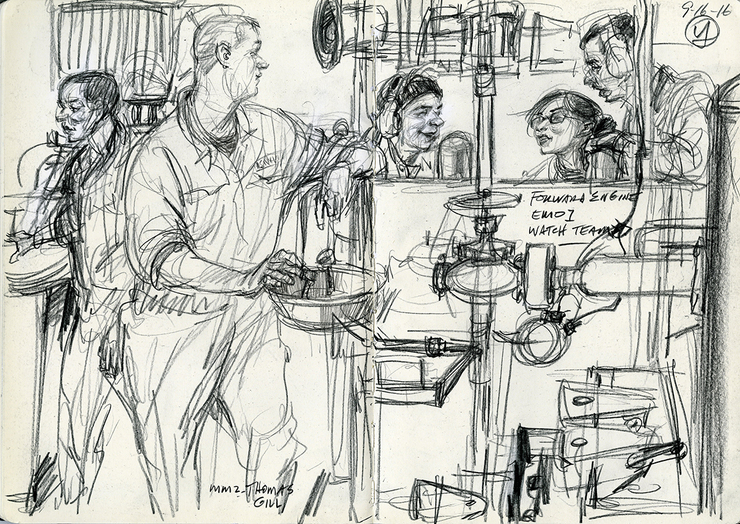

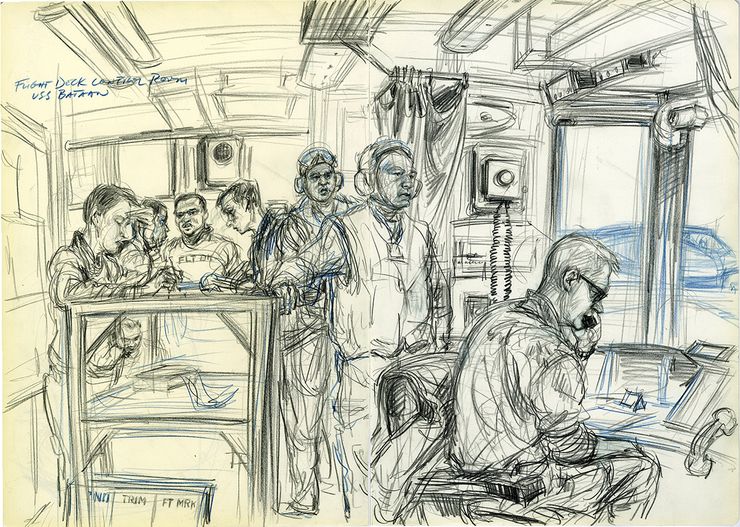

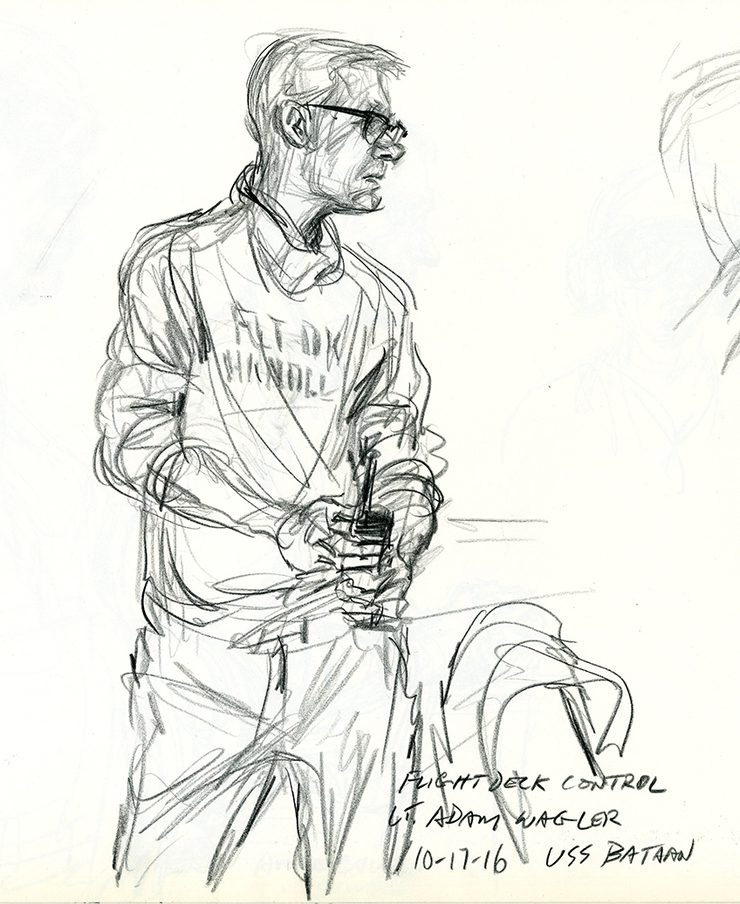

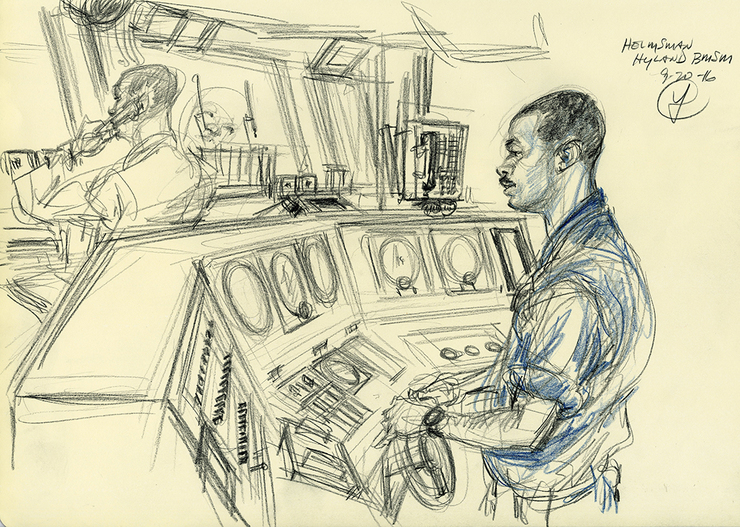

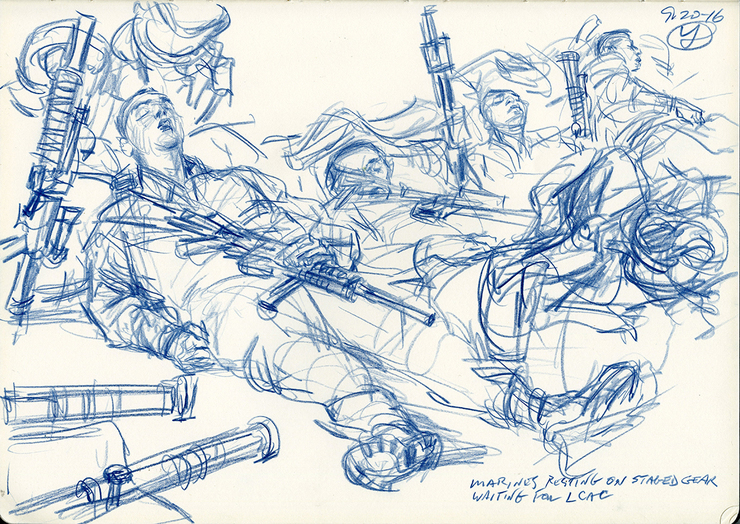

There was a hurricane brewing while we were at sea and the amphibious assault and embassy rescue drills had to be scrapped, so we didn’t have a chance to draw those. But, truth be told, we were never without material to draw. I returned several times to the flight control room desirous to capture the non-stop bustle of activity with some success. It’s not a big space and the cast of characters never stays still for more than five seconds. Doors were always opening and closing with personnel rushing in and out. It was a dodge, duck and draw environment that left me flustered but insistent on not heading elsewhere till I had material sufficient enough to bring back to the studio and develop.

Colonel Streeter got me on board a helicopter exercise, strapped to the side seat looking out a wide open door over the vast ocean. The wind and vibration was intense and it was pointless to draw as the paper would have shredded so I settled for photos and video.

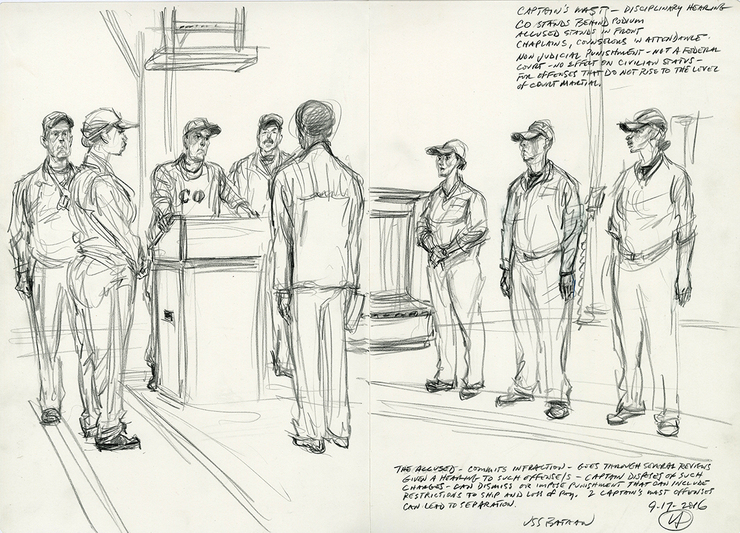

I was invited by the captain to witness a Captain’s Mast which is a non-judicial disciplinary hearing where sailors are brought before the captain to face charges and receive a judgement. It was one occasion that I regretfully forgot to use the camera as the various hearings moved briskly and my attentions were focused on capturing, in best courtroom artist fashion, the scene. I had no desire to identify the accused and instead sought to capture the gravitas of the captain and court officers.

I want to express great thanks to Captain Pfister and crew of the Bataan, the Marines of the 24thMEU, Colonels Streeter and Rideout, and to my fellow artists for the experience. A presentation of the collective artwork was made in early February at Colonel Streeter’s house to Colonel Rideout. Along with the original artwork I provided a number of flash drives containing high resolution files of all the best work and many of the sketches for the 24MEU and Bataan as well as one to Charles Grow of the Marine Corps Museum. The Colonel would divvy up the original artwork between the Marines and the Bataan. The response to the artwork presented by the artists, including Colonel Streeter’s, has been extremely positive. I hope it contributes to a momentum for more of these missions.