Our Trip to Samsø

DECEMBER 8, 2015

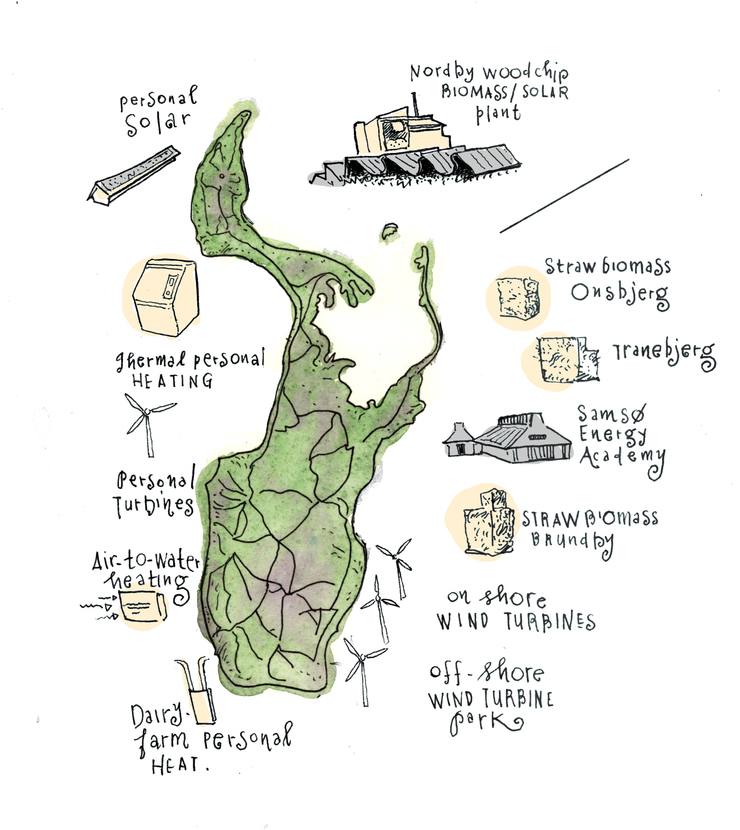

During our recent visit to Denmark Cynthia and I made a trip to Samsø Island, a place of miracles. In the late ’90’s the residents made up their collective mind to go green: develop existing renewable energy technologies to go carbon neutral and eventually carbon-free. In 10 years, not only were they CO2 neutral but were producing so much additional energy that they sold 25% of it back to the mainland . . . at a handsome profit. All this was accomplished with established tech: wind, solar, geo thermal, biomass. Clearly what they have achieved is easier in an island of 3700, where the wind never stops blowing and the sun shines much of the year. But in a salute to the world leaders meeting now in Paris Len Small, Nautilus magazine, my amazing wife Cynthia and good pal Erik Petri (who both helped in countless ways) brought back this story, appearing now online as well as in four spreads in the upcoming issue. Great help also from editor, Ariel Bleicher. Here's hoping this stimulates intelligence and resolve here and everywhere.

He brought consultants—and beer—to community meetings to try to convince his neighbors, many of them conservative farmers, to take up the cause. But the consultants weren’t getting through. So Hermansen sent them home. “Instead of telling people what they should do, I had to address the fear of change.” He told them that renewable technologies—wind turbines, solar arrays, biomass plants—would bring jobs and, better yet, money. Through subsidies, the government guaranteed a stable price for wind-generated power for 10 years, meaning investors could recoup their costs after seven or eight and start making a healthy profit.

That perked up their ears. Meeting by meeting, Samsingers—farmers, plumbers, schoolteachers, grocers—began to band together behind the project. When it finally got off the ground in the late 1990s, Samsø was putting 11 tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere every year. But by 2001, residents had cut their fossil fuel use by half. In 2003, they began exporting electricity to the mainland. Today the island produces from renewable sources 25 percent more energy than it consumes.

What makes Samsø’s story so remarkable, however, isn’t this fast transformation from carbon polluter to renewable-energy producer. It’s how it happened: Samsø owes its success not to a collective environmental idealism, but to its residents’ brass-tacks business sense.

What makes Samsø’s story so remarkable, however, isn’t this fast transformation from carbon polluter to renewable-energy producer. It’s how it happened: Samsø owes its success not to a collective environmental idealism, but to its residents’ brass-tacks business sense.

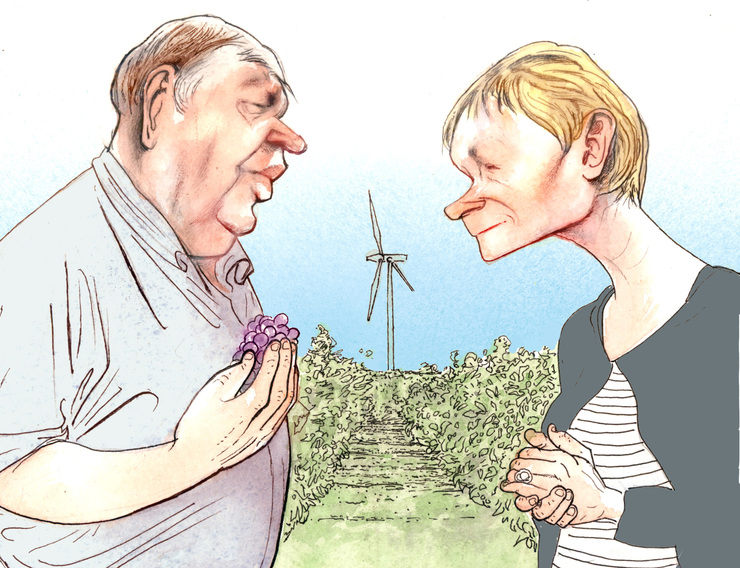

Ole Kaempe, a teacher on the island, and his wife Hedvig Hauge can see the turbine in which they invested from their farmhouse, whirring away beyond their vineyard. “Two of the wind turbines were offered to everybody; you could buy shares,” Kaempe says. “There was a lottery because too many people wanted in.”

Listening to the low drone of his turbine now, he says, he hears the “music” of income.

Listening to the low drone of his turbine now, he says, he hears the “music” of income.

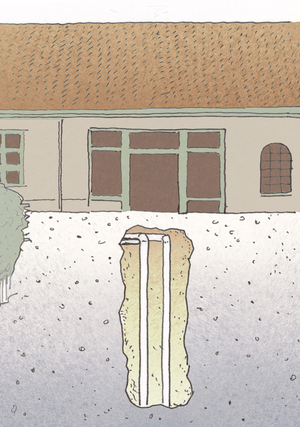

Two decades ago, most Samsingers heated their homes with oil hauled in on tankers. Then Hermansen and others got together and calculated that residents could save up to 50 percent on their heating bills if they replaced their furnaces with pumps that drew hot water, through underground pipes, from district heating plants.

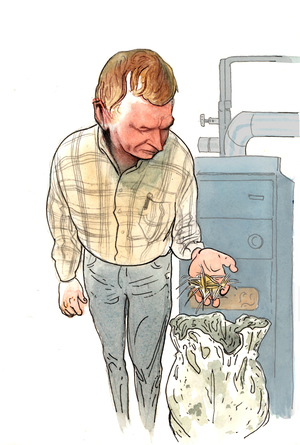

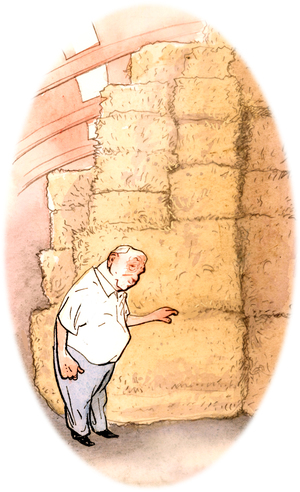

Here’s the track the straw moves on. It gets chopped very fine and sifted before burning.

The process is also, more or less, carbon neutral. The CO2 released during burning simply displaces the carbon that would have entered the atmosphere naturally, as the straw decomposed. Even the ash is repurposed as fertilizer.

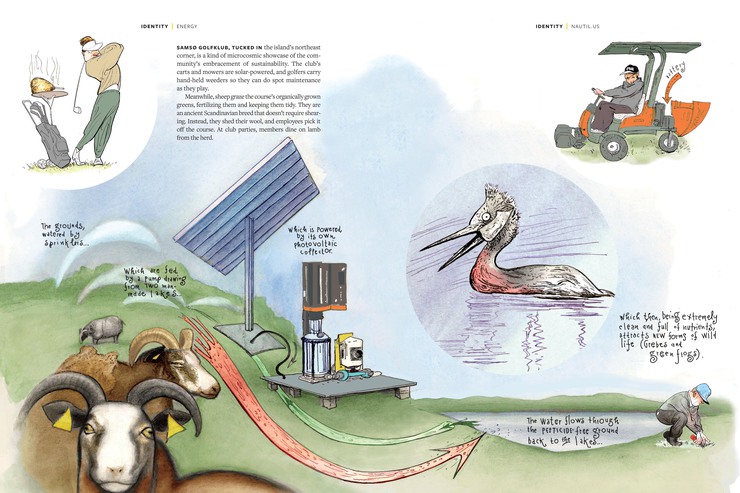

Here’s my pal Erik Petri, famed Danish cartoonist, in a solar-charged lawn mower.

No pesticides are used. Members do some light housekeeping with weeding tools while on the links.

Wonderful to meet sheep. The memory kind of lingers on.

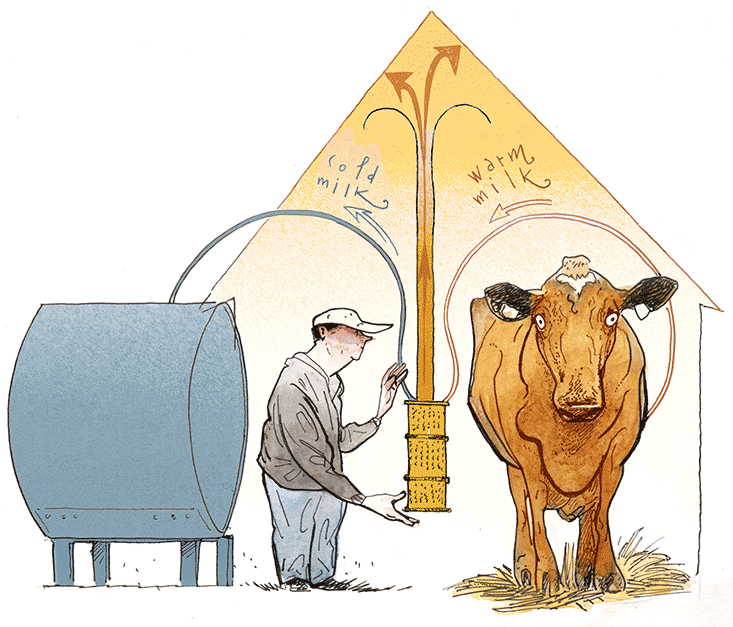

Some residents have found ways to draw cheap energy from unusual sources. Kasten Christiansen, a dairy farmer, warms his home with the milk from his cows.

“We have 2,000 liters of milk we have to chill every day from 37 to 4 degrees Celsius for storage and delivery. It comes here to this cooler, and the heat pump takes the difference in temperature between the warm milk and the refrigerant and makes the heat for the house. We’ve got pipes in the ground as well, in case we don’t have enough from the milk. In the winter when it gets below zero, we need the ground heat. In the spring, summer, and fall, there’s enough from the milk alone.”

One of the girls.

With the recent coming to power of the Rasmussen government, Denmark has gone to the Right and is defunding much of the innovative work in the country . Investors like Mr. Tranberg will be loathe to stay in the game without government incentives.

To stay true to its title of “renewable-energy island,” however, Samsø may need more help from the government. The island’s turbines are getting old and in desperate need of maintenance, but with electricity prices so low, residents like Tranberg are hesitant to buy replacement parts. Without incentives such as subsidies, Kristensen says, “there is a real threat that if an old turbine breaks down, it will be torn down instead of repaired.”

But if the Samsø model can endure anywhere, it will be in places like Denmark, where tariffs on fossil fuels are driving investment in alternatives, says Jesper Kristensen, a development manager at the Energy Academy. “You can say that we have a good model here for the rest of the world.”

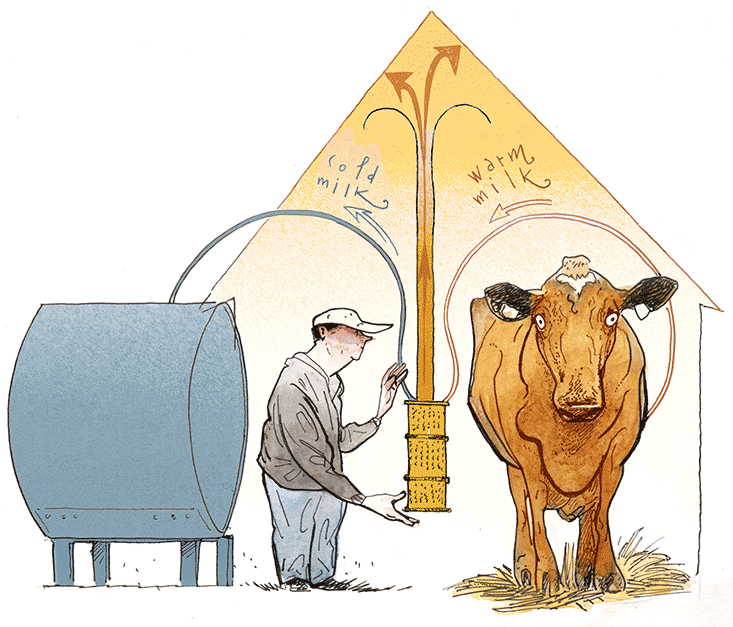

Here’s Jesper’s own heating arrangement: air-to-steam. It operates on the same principle as geo-thermal. This time it is the air from the outside that is pumped and given to a reaction with refrigerant. The moderate temperatures give him heat most of the winter (with a fireplace backup).

Here we visit the Nordby woodchip heating plant. The steam also rides through pipes going to hundreds of homes. The smoke from the woodchips is treated to greatly lessen the CO2 and particulates. The amount of CO2 released is comparable to the amount that would be natrually occurring in decomposition. Solar is the backup here. And also the Danish sheep to keep the grass trim around the panels.

Jesper explains the way this works.

Without the advice and assistance of my good friend and brilliant artist Erik Petri this trip would not have happened. Great thanks to him and his lovely wife Signe for making us feel very much at home in the sweet space known as Copenhagen.

And to Cynthia, whose love and spunky good cheer kept me on task all the way. In this time of wrenching politics over Climate Change it is important to know that our solutions are right here, in the sky, the wind, the Earth. All telling us to save it before it's too late.

© 2024 Steve Brodner