On the Spot with Special Ops (Part 1)

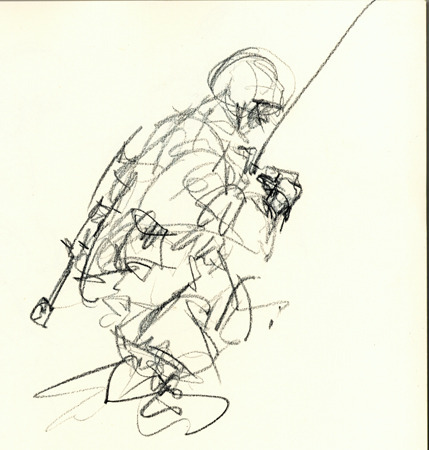

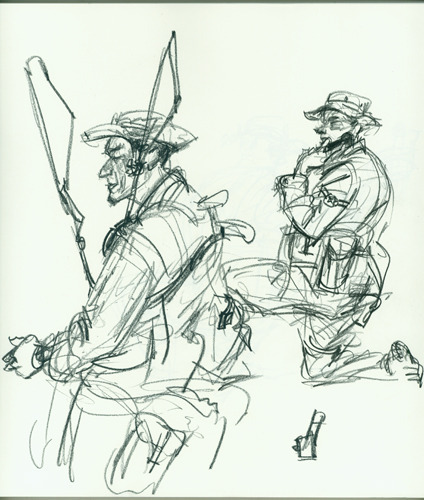

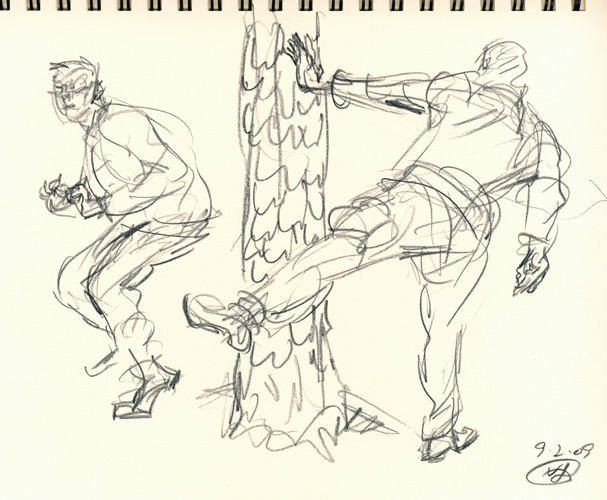

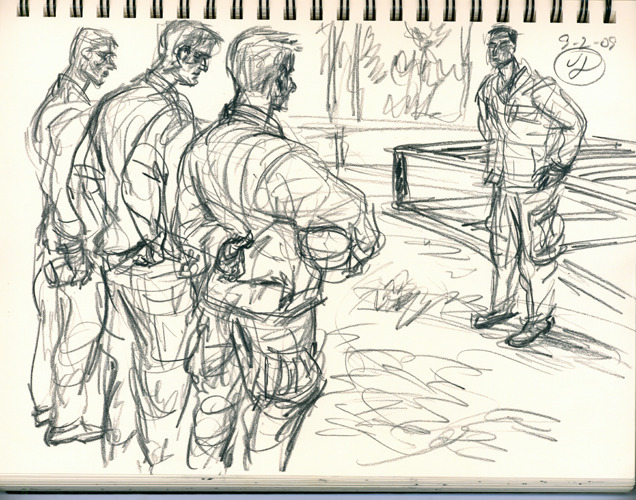

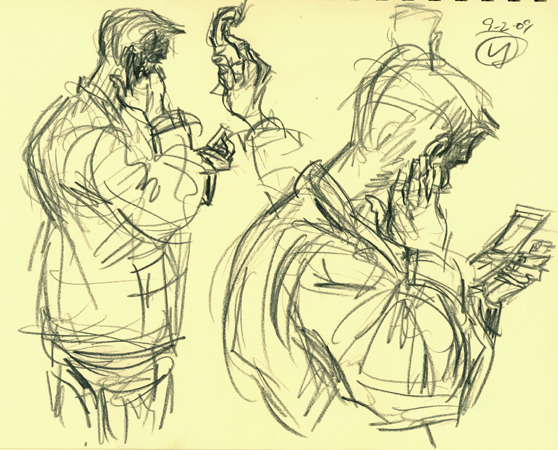

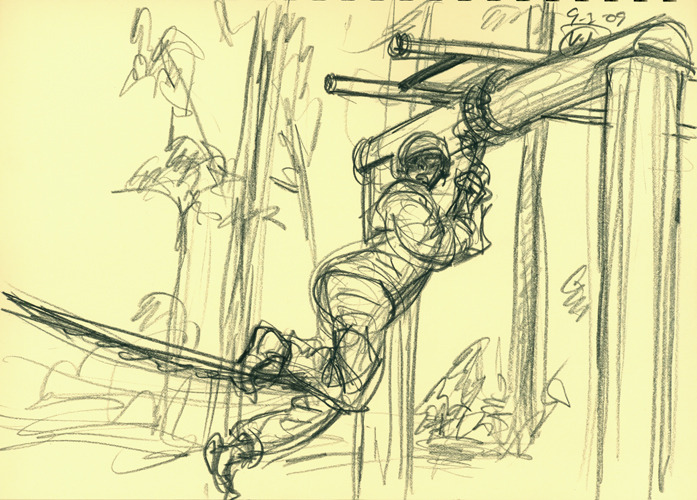

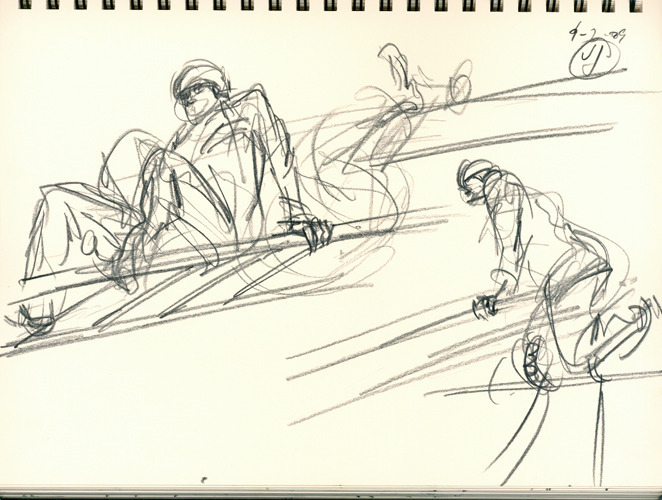

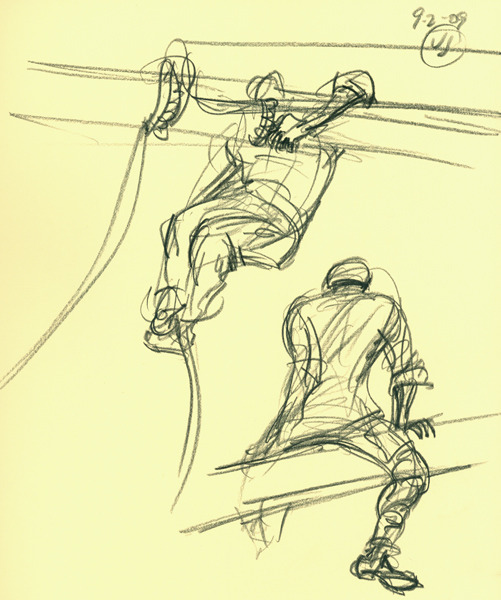

One thing that becomes immediately, and abundantly, clear kneeling, crouching, awkwardly sitting amongst several dozen soldiers, is that drawing naked models in one or two minute poses, a warm-up staple during drawing sessions at the Society of Illustrators-what we would consider “fast poses”- is light years behind trying to capture the five to fifteen second changes in position of teams of warriors weighed down with 80 pounds of battle gear. Speaking for myself, it takes a good couple of days to get over the shock of feeling incompetent and that nagging feeling of being in way over my head. The only mitigating factor is the relentless drive to keep pressing on, through repetition and seemingly reams of false starts; to learn as quickly and organically as possible, the mistakes that consume time in trying to capture the moment, and don’t advance the drawings any. Getting hung up on details may make for an award winning, meticulously rendered piece at the Society Annual exhibition, but in the middle of the chaotic swirling of bodies, it produces no more than a couple of aborted lines. As each assignment and circumstance is different, so too is the way one responds to the challenges. If the possibility for a downwardly spiraling, confidence shaking, mind fuck can be corralled, eventually satisfying results happen and you feel like you’ve found the zone and can build on it. Unfortunately, at least for me, more often than not, no sooner have I entered that zone with the clear sense that in a few more days I could get real dangerous (in a good way), than the trip is over, I’m packed up and heading home. If there has been one regret with these assignments it has been that they are not two weeks in length, minimum. The first few days would be to work out the bugs and insecurities, the remainder of the time to just let it rip. Still, I’m not complaining. Every one of these trips has been a remarkable event and learning experience.

As a member of the Society of Illustrators and as a humble participant in its Government Services Committee, I have had the pleasure to become, in the past few years, a contributor to the United States Air Force Art Program, which sends artists out on location to visually report on the work of the armed forces, in particular the US Air Force. The artwork created eventually, upon acceptance, become part of the permanent collection of the Air Force at the Pentagon and other military bases. I saw my potential in the USAFAP, in large part, as an opportunity to contribute in a small way to the tradition of the challenging craft of on-the-spot drawing. Reportorial illustration has always appealed to me, very likely because of the excitement in its immediacy and energy when done right. One of my dear friends and mentors from Parsons, Bernie D’Andrea, seemed to intuit from my class work that I was in my best element during the drawing process. My final illustrations in his class often fell short of the energy and inspiration the initial drawings had. Bernie was always stressing the importance of our personal “marks” we make during drawing- and his mantras about understanding those marks we make as extensions of our language, our personal visual conversations, remain with me to this day. The work of Howard Brodie, another great friend and mentor, probably CBS-TV’s greatest combat/courtroom artist, remains a significant influence on me no matter what kind of illustration I am involved with at the time. I use him as my benchmark and strive to achieve an approximation of that quality when given the opportunity to do reportorial work. And those opportunities have been provided in large part by the USAFAP.

It is easy to take for granted the security of a studio environment, where a drawing or finish can be, if necessary, reconsidered and restarted till the desired effect is achieved. Time is, in a sense, suspended, when we can restart from scratch, an image. All that has happened is that we are back at square one, the process replays, and, hopefully, the revise will produce an improved image. But in reportorial work, the trick is to capture the moment that will not happen again, as events in real time don’t do retakes. Great reportorial artists have that special capacity, that gift, the result of an immersion in the craft, to capture the essence, to encapsulate the significance of an event in the well-observed telling gesture.

This is a long way of saying that my most recent assignment, which involved going to Fort Bragg/Pope Air Force Base, Labor Day Week, in North Carolina, to draw Air Force Special Ops Forces in training was quite a challenge. A group of six illustrators from around the country, Paul Smith, Vivian Nguyen, George McCowan, Christine Murphy, Jim Balleto, and myself, was assembled and arrived Monday, August 31st. Our liaison for the week, someone I’ve already had the pleasure of working with at Camp McGregor/Fort Bliss last year, was Bob Crawford.

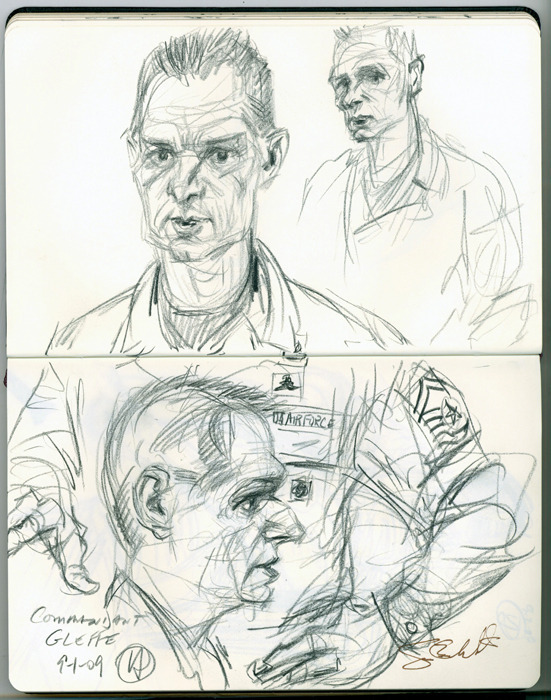

We were introduced the next morning to our host, Senior Master Sergeant, Sean Gleffe, also addressed as Commandant, of the 342 Training Squadron, USAF Combat Control School. He runs the show there. Bob told us that SMSgt Gleffe probably manages more responsibilities than most officers with higher rank. The Commandant’s very soft-spoken and gracious demeanor couldn’t mask an intensity and laser focus required to shoulder the responsibilities of training an elite group of men, ranging in all ranks, who volunteer to serve in the “First There” (their motto) Combat Control Unit. By “First There” I mean these are the elite forces that drop behind enemy lines before the shit hits the fan, set up a control operating locations from which they coordinate air strikes, determine the ground conditions in establishing landing zones, take offs, troop movements, you name it. Essentially, in layman’s terms they are the eyes, ears and brains behind all operations to follow. The advance advance team- the crucial link to making or breaking a successful operation. They accompany SEALS, Rangers, Green Berets, and provide support for the Marines. The responsibility on these elite units is enormous and by extension, the responsibility resting on Gleffe and his crack team of instructors is even more enormous. The physical, mental, and psychological conditioning is strenuous and unrelenting and the attrition rate in the school is significant, but not as brutal as we originally thought, in large part because of the vetting process prior to entry. My thoughts at times observing the exercises were “It’s great to be young” and “It’s great to be in such incredible physical condition”. Our other host, First Sergeant Charles McHarney, was an equally gracious and helpful tour guide. He was constantly peppering trainees with questions and showed little patience in suffering meandering answers from the students, yet his heartfelt involvement with their wellbeing and future success was in abundant demonstration. Good people all around.

We received a personal (from Commandant Gleffe) and video presentation explaining the school and its mission, a tour of the historical center housing artifacts form Special Ops history, were present for two Forward Air Traffic Controller exercises, an obstacle course training exercise (that really drove home how out of shape I was), and parachute jump set-up and preparation. I was especially grateful that we had an opportunity to be present for a second Forward Air Traffic Control exercise as the first one, on the first actual day of working, proved to be incredibly frustrating. Negotiating the windy conditions on the ground while trying to draw, trying to get a grip on the swirling pace of units parachuting to the ground, establishing and securing positions, cargo planes making short landings and takeoffs, and remembering to use the camera (oh yes, a camera was essential) for future detail reference felt like an Ed Sullivan Show plate spinning act. Only in this circumstance they were crashing to the stage. I had a headache that night going to bed, my confidence in tatters. My good fortune was that the second exercise occurred on our last active day and by then I felt like I was hitting a stride and walked away feeling pretty cocky and wishing that more could follow. Repetition does make for more confident, better work. I often wondered, in the middle of the swirl, how Brodie could manage those incredible drawings in the middle of battle- with no digital cameras and laptops available- and then had to put it into perspective that he had the entire battle of Guadacanal, in fact he had four years of constant action to master the working conditions. I also realized by the last day that I wasn’t drawing any faster per se- that was an illusion. What had happened was that I was embedding to memory the uniform and gear, and where things hung or were strapped, and with that embedding came the freedom to capture the gesture first, unconcerned with details of gear placement- that could come later. Therefore, the lines moved more flowingly, unchecked from those technical considerations. Frankly, rendering gear wasn’t what these sketches were about anyway. It was capturing the frenzy and movement and descriptive gestures that could tell the story of the intensity of the training. Also noted during this trip was that with each assignment comes a better grasp of coordinating photography with the drawings. For my concerns, I’m not looking to make artistic, journalistic statements with the pictures I take. They are first and foremost there to provide detail and informational reference. The trick has been to develop the discipline to remember to quickly break from the sketch and get a few shots of what I am drawing from as similar a vantage point as possible. As I generally confine myself to colored Prismacolor pencils, paper becomes a crucial factor as well. Only within the past two years have I discovered the joys of moleskin pads. They contain amazing quality paper, excellent for pen/ink, pencils, and watercolor. The drawback is that they don’t come any larger than 8x10 inches. When I did courtroom drawing, and especially after comparing notes with Howard Brodie during the Hinckley trial, I gravitated toward Strathmore smooth Bristol paper pads. I have since found the smooth Bristol to be difficult to get hold of in art supply stores and the regular medium surface pads inconsistent with a tendency to resist a smooth flow of the pencil line. Before leaving for North Carolina on a whim I did pick up a 9x12 inch Cachet sketchbook with beige Canford paper which I didn’t use till the second day growing increasingly frustrated with the look of the drawings in the other pads. It turned out to be a revelation and a joy. I had hit the sweet spot, and whether or not it was a coincidence that my confidence and sense of control also accelerated on that second day didn’t matter. The paper allowed for the pencils to glide like a skater on the surface. There was no holding back. I am checking into whether they make larger size pads because they will be my staple the next time I go out on one of these ventures.

While I’m certain that some of the eventual finishes will be more thought out, rendered-posed if you will-images, like what I turned in for the last presentation to the Air Force, I hope to include, with minor modifications, a healthy selection of the more successful sketches as they contain an energy amid all the dashes, wiggles, zigzag lines that can never be replicated in a more formal piece.