The Embed in the Stan

July 28, 2012.

A year ago today I was on my way to Kabul International Airport, Afghanistan.

It seemed perfectly natural to be heading there and at the same time it seemed perfectly crazy. Other than my Marine son, the rest of the family saw it as some sort of death wish, or postponed mid-life crisis exercise coming to fruition. Something I needed to get out of my system. Something I, an admitted life-long coward, needed to prove to myself. From where I stood, at 57 years of age, realizing that I wasn’t getting any younger, these concerns seemed perfectly arguable and, in fact, on point.

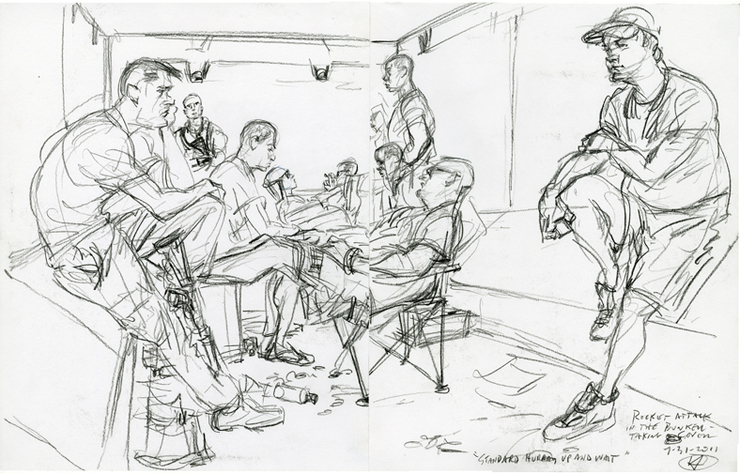

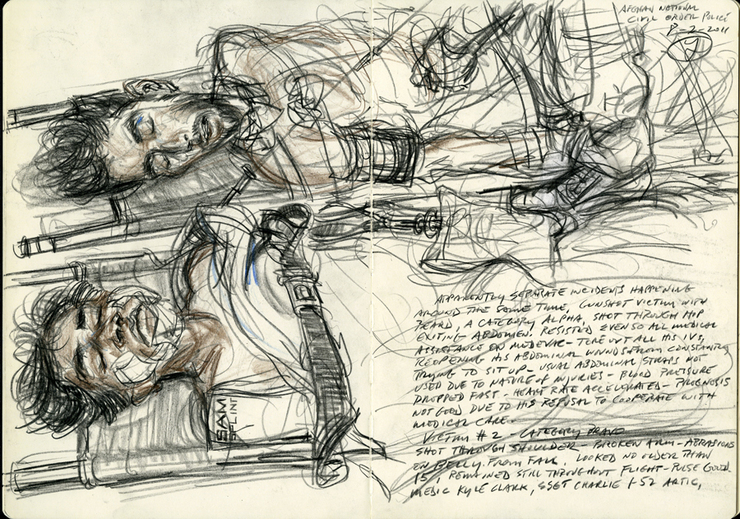

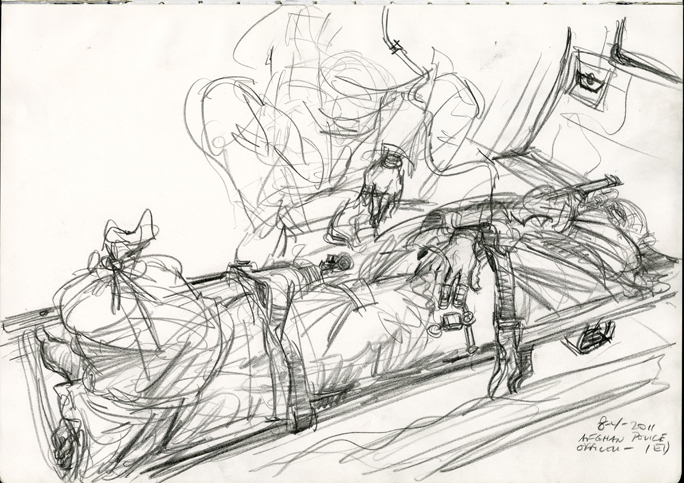

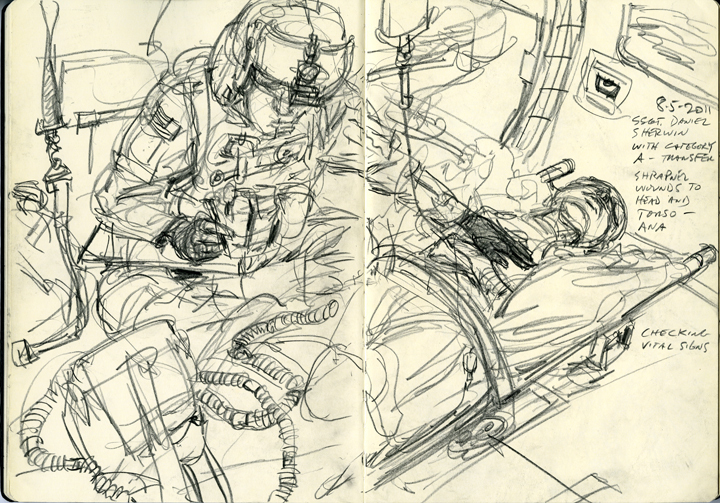

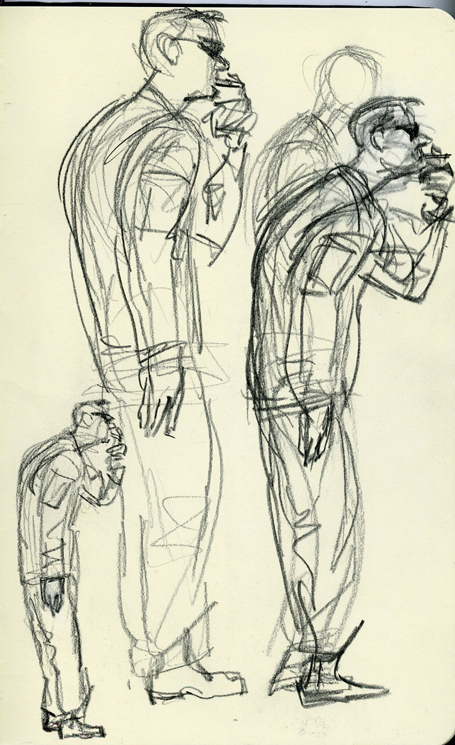

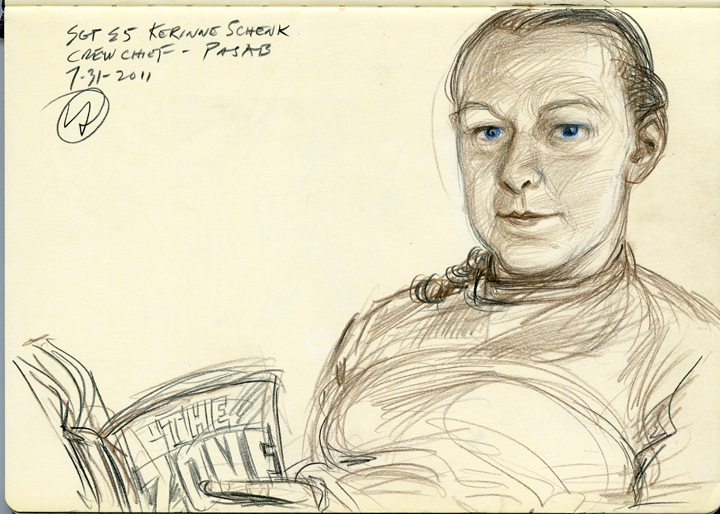

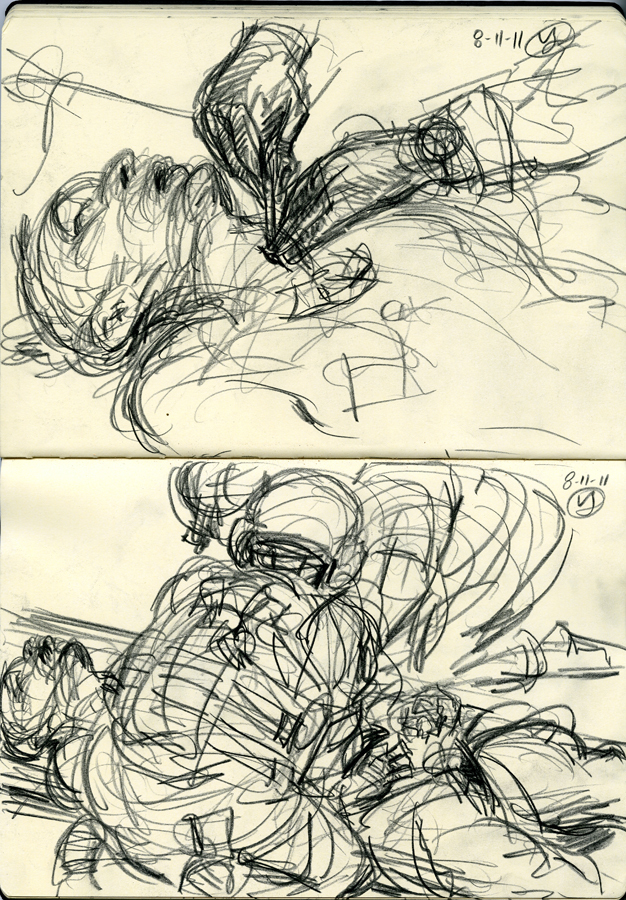

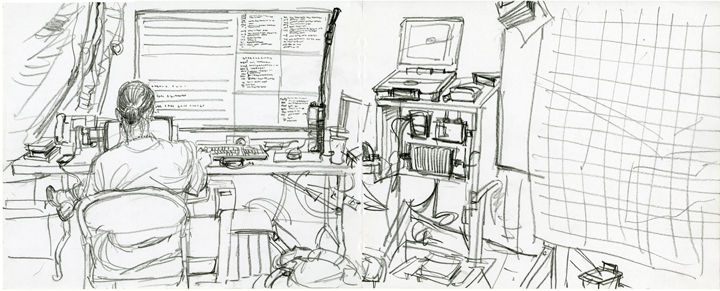

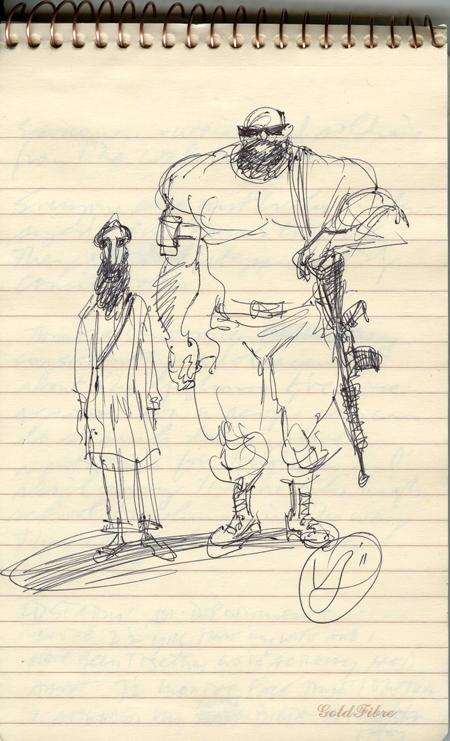

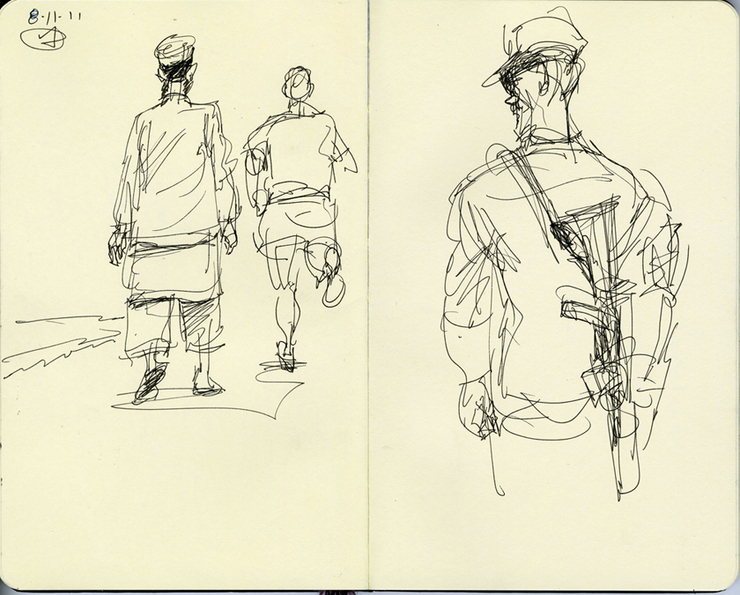

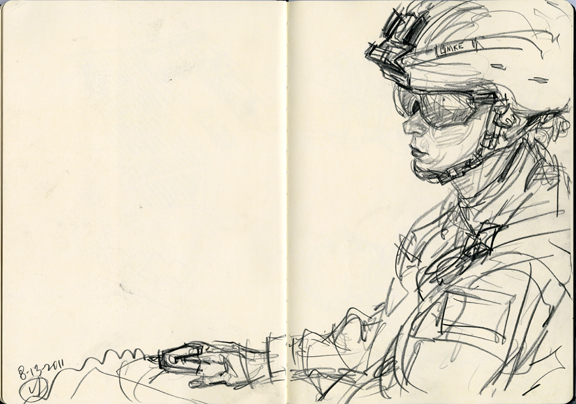

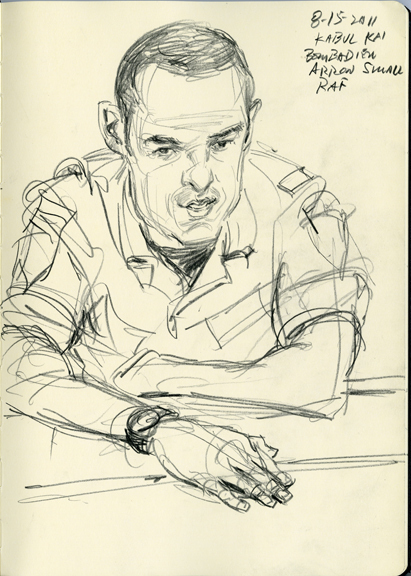

My wife, Terri, while not enthusiastic and sharing the already mentioned reservations, also read this adventure as a logical extension of the reportorial work I had already been doing for several years working with the USAF Art Program through the Society of Illustrators of which I am a member. Artists, in small groups, going on assignments to bases around the country, sometimes overseas, documenting in drawings and paintings the various operations of the Air Force. Rendering planes in the sky or on the ground had not been what drew me to the program. I was looking to draw real people who happen to be warriors; to witness and create images both on the spot and back in the studio telling their stories with the added benefit that the artwork would eventually become part of the permanent collection of the Air Force. My favorite assignments up to that point were the training exercises for Urban Operations, Combat Control and ParaRescue (PJ) teams.

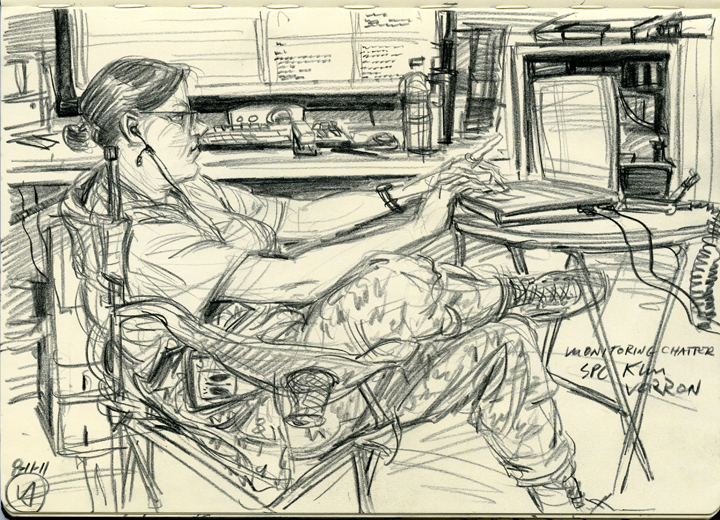

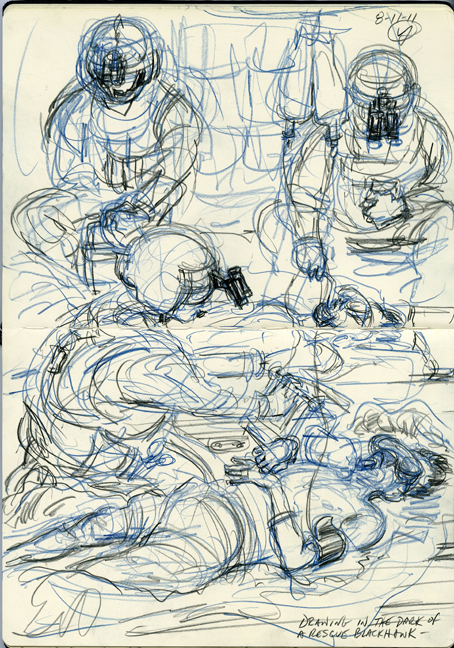

Some of the assignments, however, could also feel like group tours with the artists moving from one location and task to the next without the benefit of absorbing the energy of any one setting and developing a sense, that comes with repetition and familiarity, of what to look for and where to be when it happens. Being part of a group often also meant dealing with various agendas and individual levels of enthusiasm and energy. I would find that my best work happened once I managed to break off from the pack and linger at one spot, or, as with the PJs, meet up for late night exercises after the other artists had gone to bed. The seed was planted during these moments that I could do so much more if I had a chance to embed in one spot with one group for an extended period of time, and that when returning home I would not have the nagging feeling that my momentum and skills were jelling just as the assignment was coming to an end.

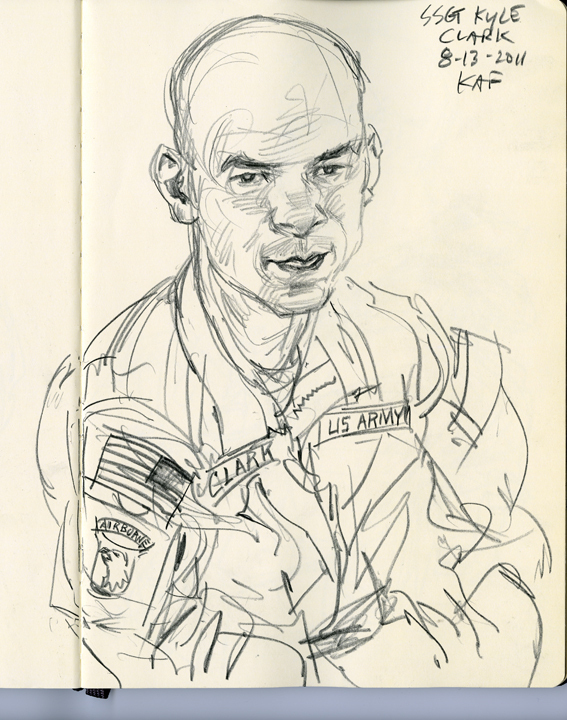

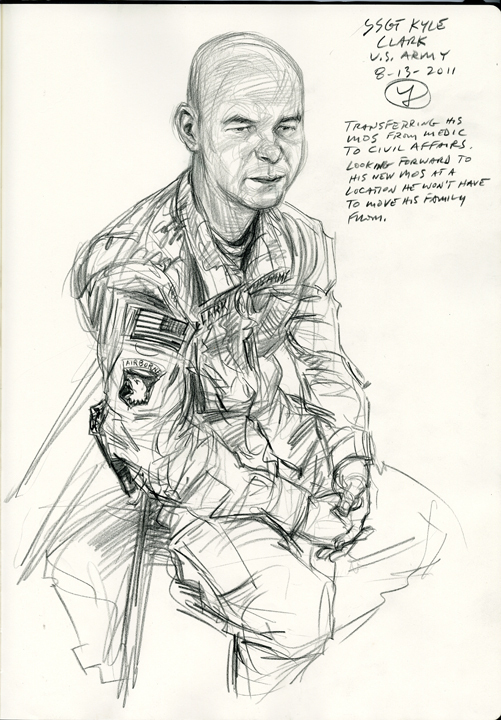

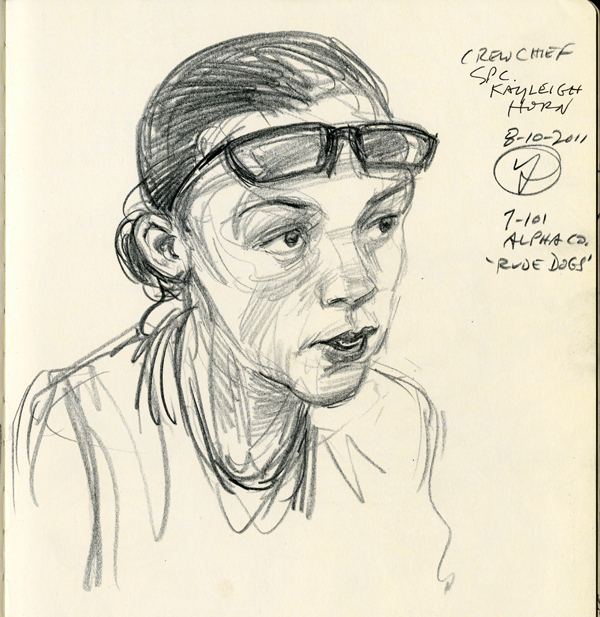

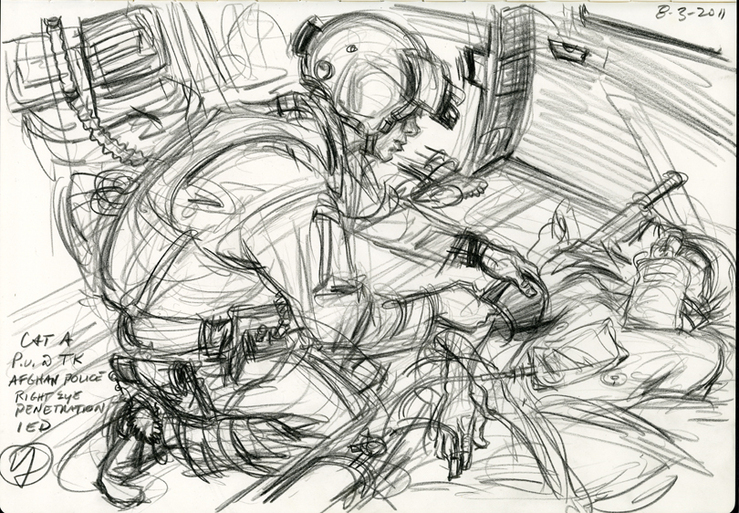

These Air Force assignments were also overlapping with my work with Troops First Foundation, a troop support organization founded by former ad executive Rick Kell and former golf pro and CBS PGA commentator David Feherty, whose columns for GOLF Magazine I'd illustrated since he began writing for them in the mid 90's. This long term collaboration with David had forged a close friendship over the years and in 2008, and then again in 2010, he invited me to accompany TFF on tours of Iraq and Afghanistan respectively ( I have since done another one last Thanksgiving in Kuwait.). My function was to tag along and draw the soldiers and Marines during these celebrity golf pro meet and greets. I took down names and addresses of family and loved ones and, upon returning home, tweaked the originals, sometimes redrawing those that proved unsatisfactory on second look, scanned them for my files and mailed the drawings to the designated recipients.

The Troops First assignments were remarkable if for no other reason than I was on location in places I never would have expected to actually visit in this lifetime. We were given protected Camp Cupcake VIP treatment at the various FOBs. The drawback, again with these celebrity meet and greets turned out to be even more hurried affairs with scant chance to absorb what I was witnessing. On any number of locations I found myself thinking that I could easily set up shop and spend a couple weeks drawing. The Thanksgiving week trip to Helmand Province further solidified a desire to do an extended stay.

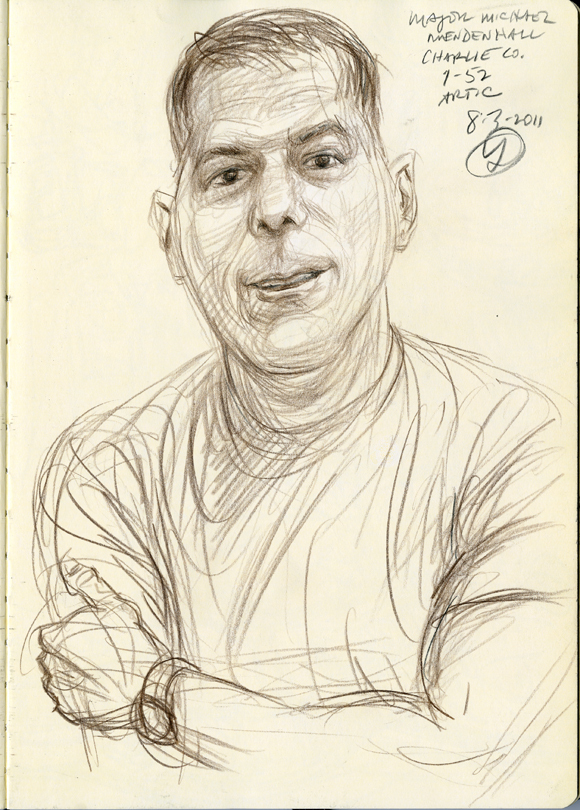

It was in Afghanistan with Troops First that I met Major Patrick Zenk and his Army MEDEVAC team at Camp Dwyer in Helmand. I was completing a portrait of a soldier when he came up and with all seriousness asked me to do a “fast” drawing of him and his team by their Blackhawk. “You know, a quick sketch. A few lines.” I explained, with a laugh, that a 'fast' drawing of them with their Blackhawk in the short time we had remaining at the camp was a no go, but promised to do something based on photos I brought back with me. It turned into a pretty large watercolor, which I scanned and sent in high-resolution to Major Zenk and his team. They were impressed and appreciative and he invited me back to embed if I ever wanted to. I followed up on that invite a few months later with an email to Major Zenk. His reply was that a hot cup of coffee and a bunk were waiting. Unfortunately, by the time my media request to embed with them was in the system, their schedule was booked solid with journalists and they were to be returning home by mid summer. Major Zenk strongly suggested embedding with Major Michael Mendenhall and the 1-52nd Artic Dustoff in Kandahar as a Plan B. The new request was put in and approved.

Media requests require an accreditation from a bona fide media organization that they are sending you on an assignment. I approached Peter Kaplan, for whom I worked for 15 years doing front-page illustrations when he was managing editor at THE NEW YORK OBSERVER. He had since moved over to Fairchild Publications overseeing fashion mags, but Fairchild was part of Conde Nast and Peter felt the story had possibilities for GQ. That said, Peter was initially resistant to signing on for me. “Vic, I know Terri. If something happens to you, I’m the one who’ll have to call her. I would never forgive myself for giving you permission to go there.” I told him not to worry- a helicopter was the safest place to be, and I rattled off statistics to back me up.

Former Marine and combat artist Michael Fay, whom I first met while giving a talk to a Hartford MFA Program class a few months earlier, was good for much advice on speeding up the process of getting the request approved. Apparently, naming a specific group to embed with and their location was a big plus. Vagueness doesn’t work well with military public affairs personnel. I had the group, their commander, and where they were stationed. A visa was required from the consulate for Afghanistan in Manhattan. That took about a week or so and required leaving my passport for the visa to be affixed inside.

NATO/ISAF (International Security Assistance Force), approved the request and the ball was rolling. I next had to find the best flight over there. It’s funny how if you just stand back a bit you find that things fall into place in strangely coincidental ways. Joan Kilberg, the mother of my promotional consultant at Agency Access, Jennifer Kilberg, also happened to be the travel booker for decades for the National Geographic photographers. How could you go wrong with that expertise? She worked up the best flight at the best rate she could find and made that part of the process a breeze.

Michael Fay provided me with the Kevlar and first rate body armor- called dragon skin- from a friend who had just returned from a tour. For a couple months I wore the armor when I hiked or did my morning walks up and down the road to build up stamina. The substantial sweats I worked up back home training with the body armor were nothing compared to the full force of the August heat in Kandahar. Simply no comparison.

There was just one glitch. My public affairs contact in Kabul informed me that military escorts were no longer meeting journalists at the airport. I would be on my own till I arrived at the other end of Kabul International where the military base and airfield were located. Also, while promise of staying on the base till you departed for your next location was not a guarantee. I may have to find lodging in Kabul if I wound up hanging around for more than a day waiting to transit. This did not seem like fun- especially to my family. They knew only too well that I am not an Alpha dog personality and were convinced I’d wind up doing something wrong and turning up on some hostage snuff video. Steve Mumford, a brilliant combat artist/journalist, offered suggestions of places to stay in Kabul if necessary, hotels run by members of the Australian Special Ops. Cool. Sort of James Bond-ish. The caricaturist Roman Genn, who had also done several embeds in Afghanistan, took care of the concerns about arrival by hooking me up with J.D. Johanes, former Marine and combat journalist, who in turn hooked me up with his friend, Mohammad, a Hazara, who would meet me at the airport. Within a half hour of J.D.’s email, I received Mohammad’s very savvy email of introduction which started with, “Yo, Bro….”. I was feeling much better. I was pumped. I had a homey waiting for me.

I returned from Afghanistan with a lot of notes, volumes of pictures, and many drawings. Peter Kaplan suggested I just start writing and putting everything I had in my journals down on paper. Editing would come later; it was important first to unload all the impressions while keeping in mind that I should avoid at all costs the trap of writing the great American novel. Think key events. Maintaining the focus on telling my story was a complicated affair as I had also returned to my studio life juggling deadlines for publications. The months started adding up though I intuitively felt the right opportunity to make a pitch would happen at the right time. That time happened when I did a major piece for Fred Woodward at GQ, which I blogged about last December under the title, “The Grand Opus”. It was a spoof of the Sistine Chapel and the debt crisis. The illustration turned out very well and Fred was extremely pleased. His enthusiasm was amplified by praise from editor-in-chief, Jim Nelson. Taking advantage of all this positive energy I pitched the idea to Fred over the phone. He was very receptive and asked me to forward copy and images. Fred worked up a layout to present and I worked with the editor’s suggestions to limit myself to 5 segments of approximately 500 words each. This I did.

Despite the enthusiasm, it was decided not to run the article in the print version of the magazine. Fred had great faith in the material and wanted to post it as a GQ app for iPad and eventually to post it on GQ online. Fred handed over the task of putting together the app- the first of such a scale, to Jeffrey Kurtz, who did a magnificent job. He worked tirelessly on it and deserves the credit for making it flow so well.

My story was fact checked relentlessly. It felt like every line was combed through for veracity. I provided names and email contacts for members of the MEDEVAC crew and of anyone else I quoted. Terminology was double and triple checked. Phone calls or emails became more frequent as Jeffrey got closer to the publishing deadline but I never felt annoyed by the follow up questions- in fact I felt awed by the journalistic professionalism. My copy was left largely intact but the editorial tweakings were perfect and added clarity. I want to thank Michael Allin, Lu Fong and Rafi Kohan for their work.

The story is now online.

It seems to have lost a couple of the features that the app provided including a sidebar on noteworthy combat artists put together by yours truly as well as some video. The app is still available for purchase, as part of the digital edition, on your iPad- assuming you have one. Regretfully I don’t.

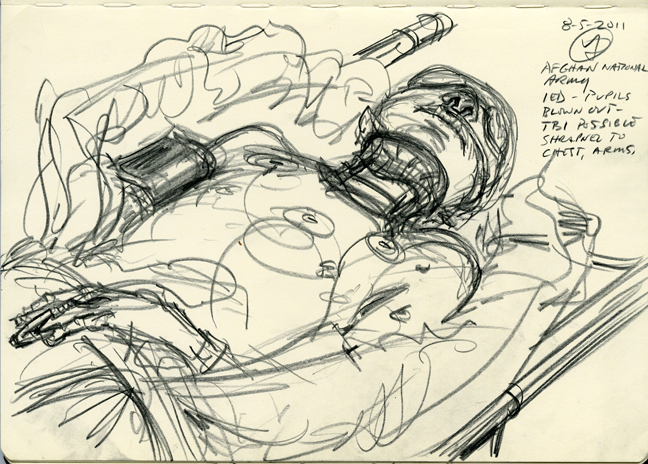

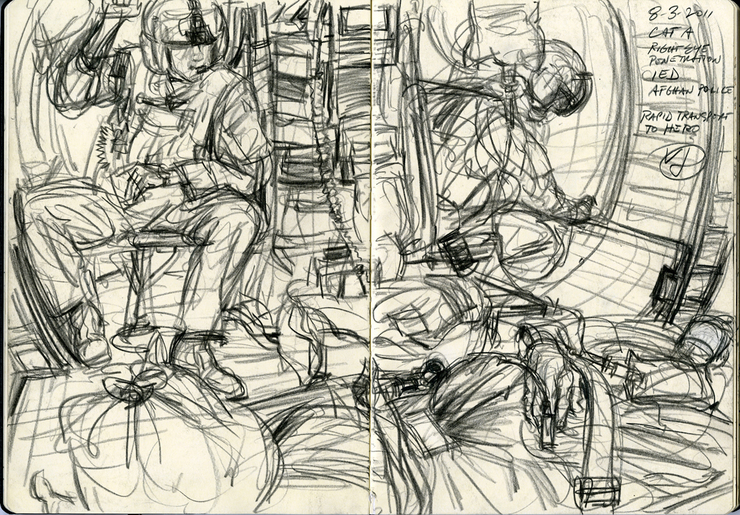

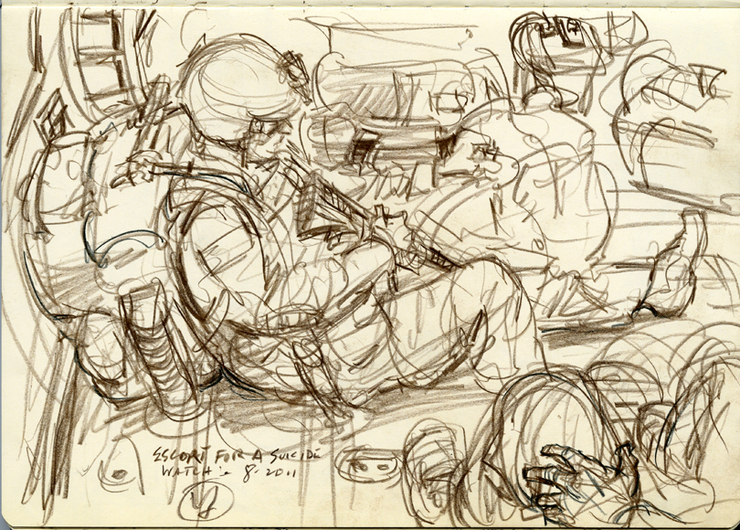

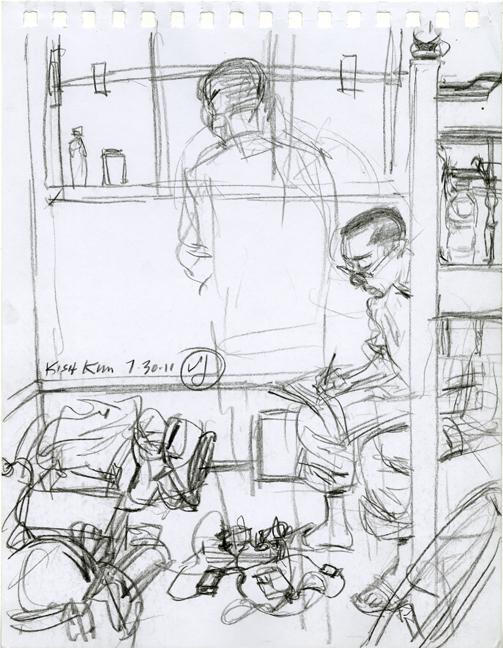

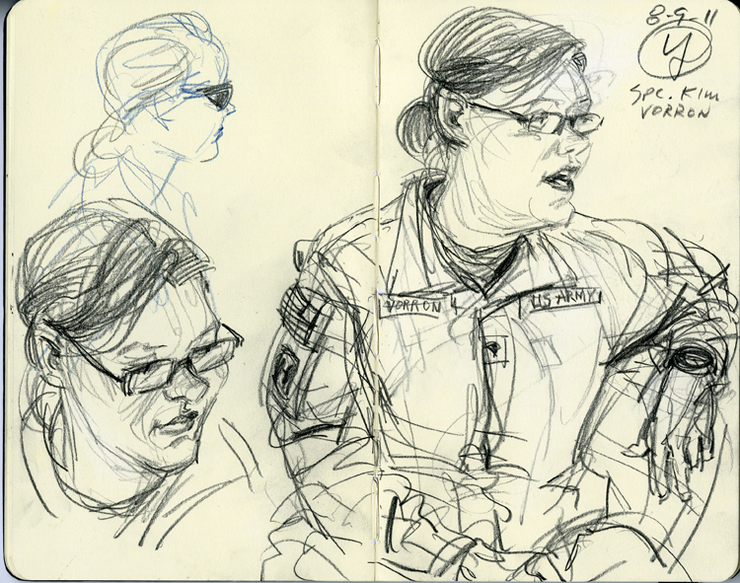

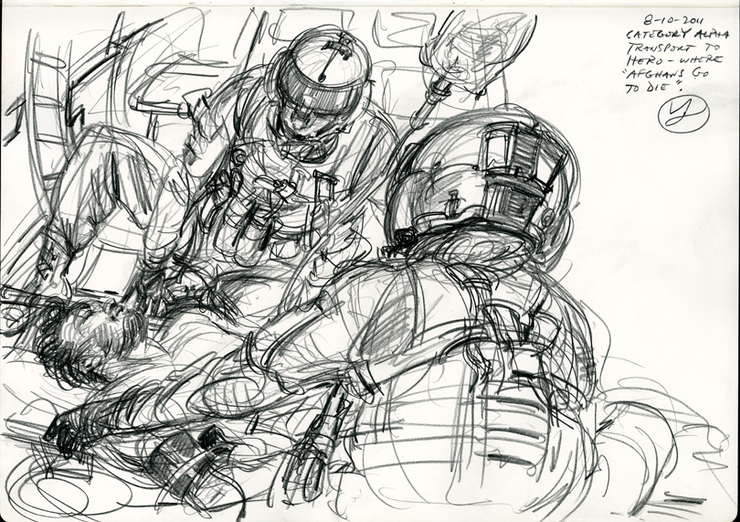

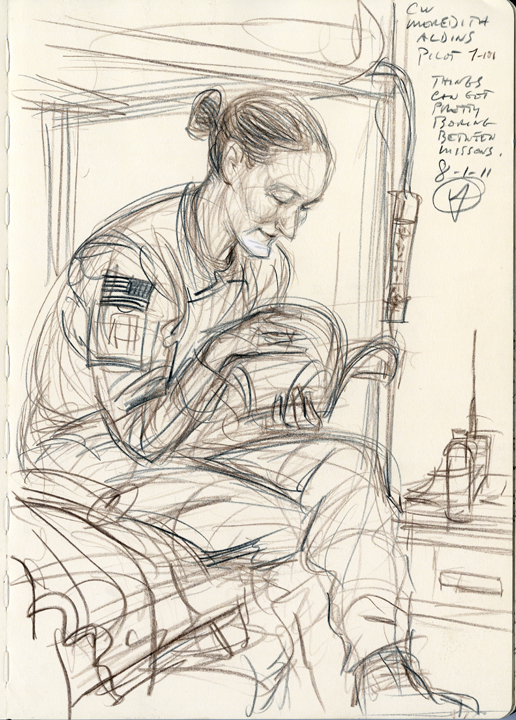

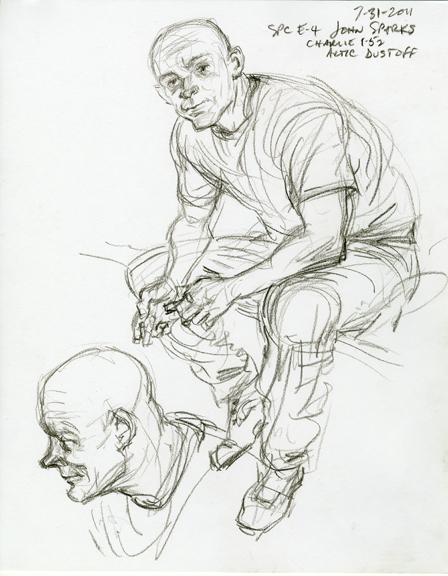

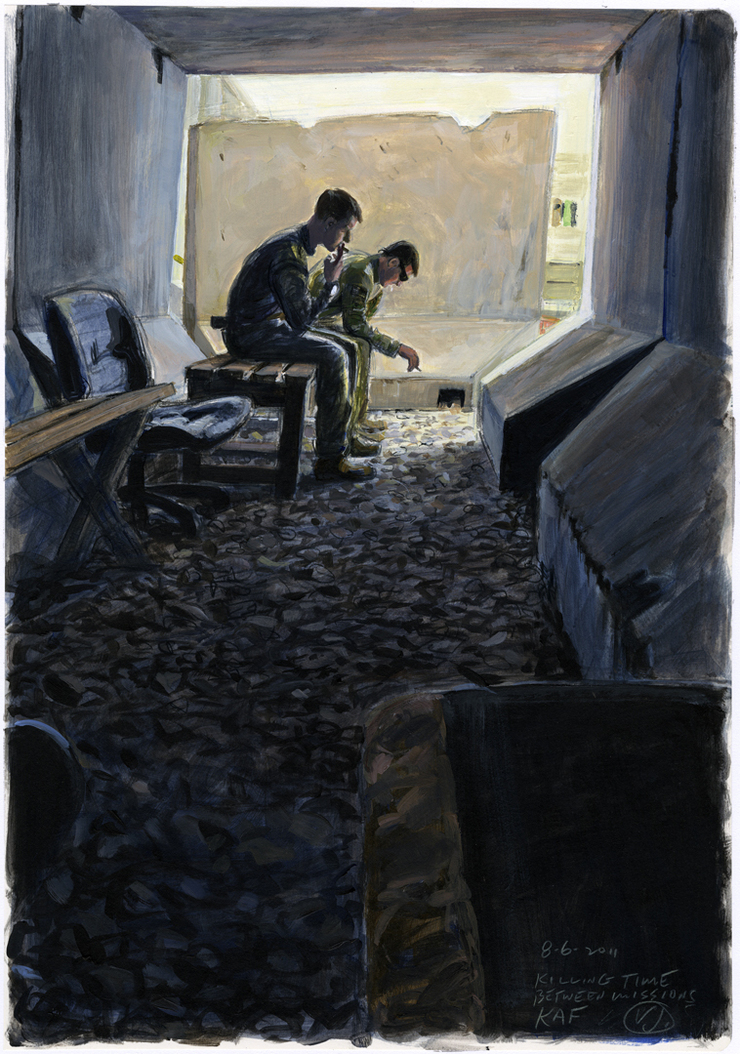

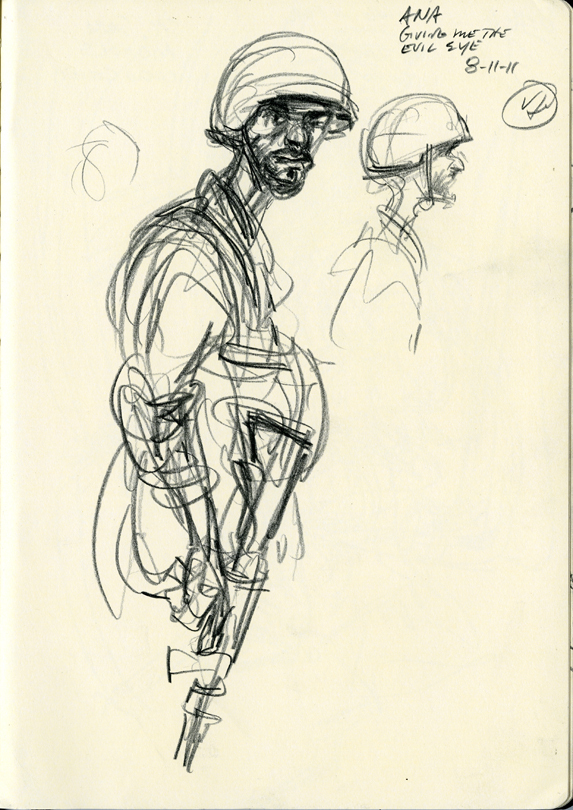

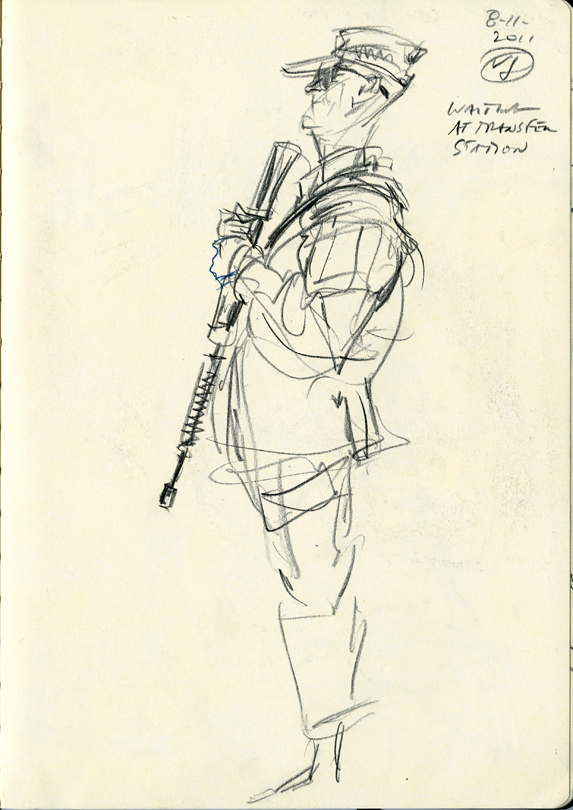

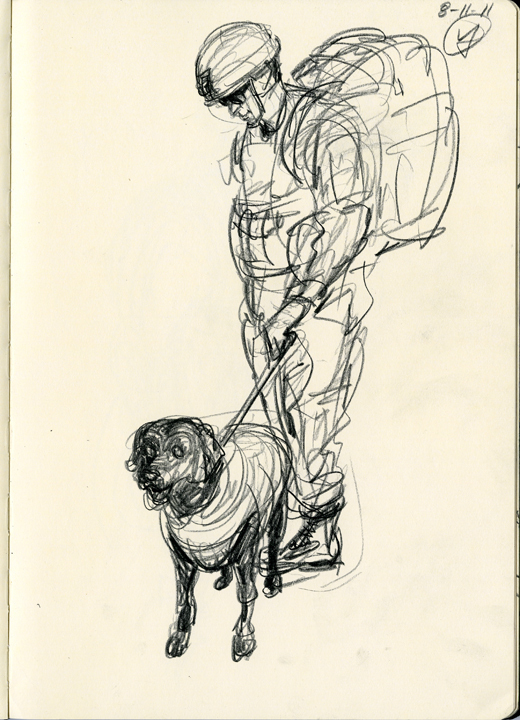

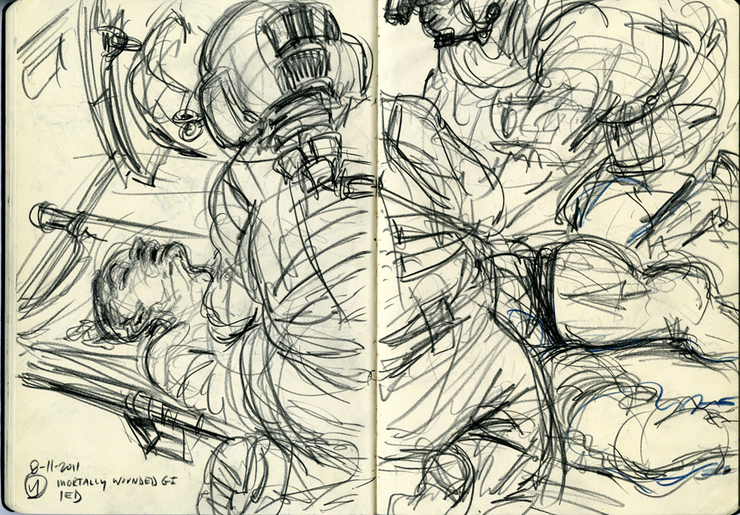

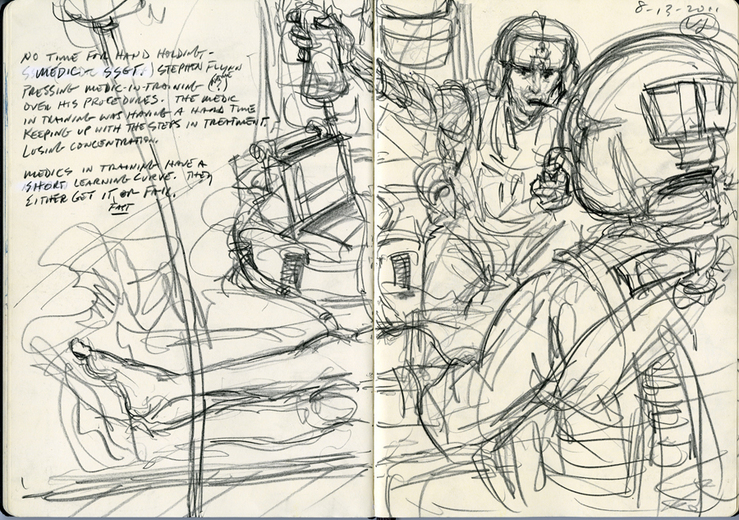

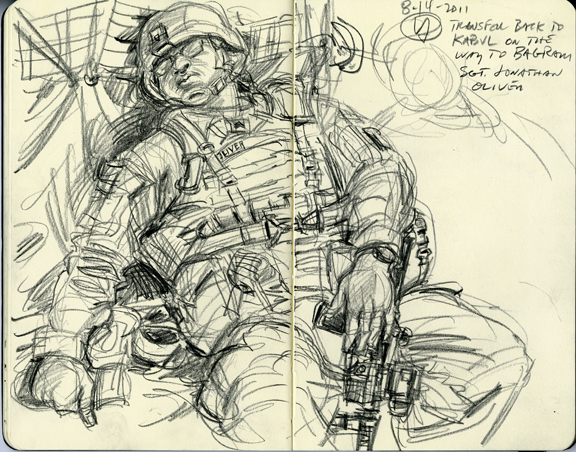

GQ ran a sizeable number of the drawings but I will add some of my favorites here that didn’t make it in. It took almost a year from embed to finally getting this article published and, apart from showing some close friends and confidants under the right circumstances, I’ve pretty much sat on this body of work so as not to compromise publishing them. So much has been learned from this experience in combat journalism from writing up a request to the final review of content before publishing as well as understanding the sometimes brutal logic behind editing and keeping story flow moving- so many names and observations were taken out.

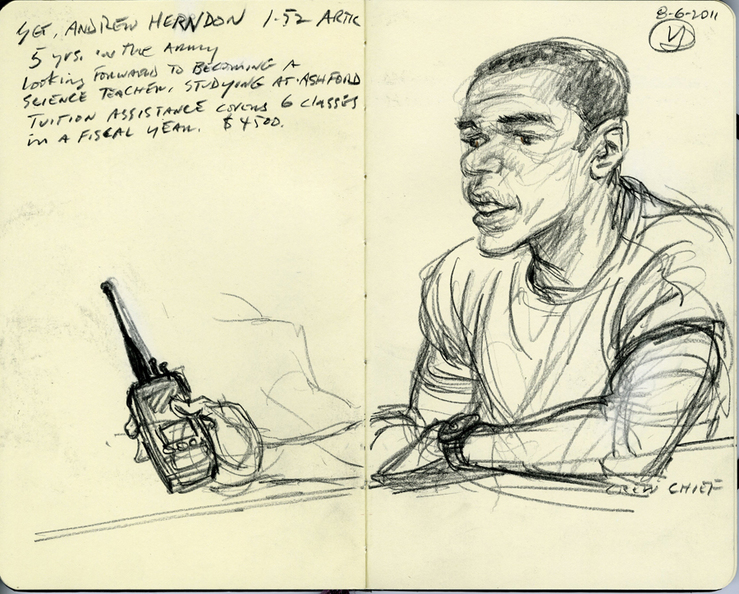

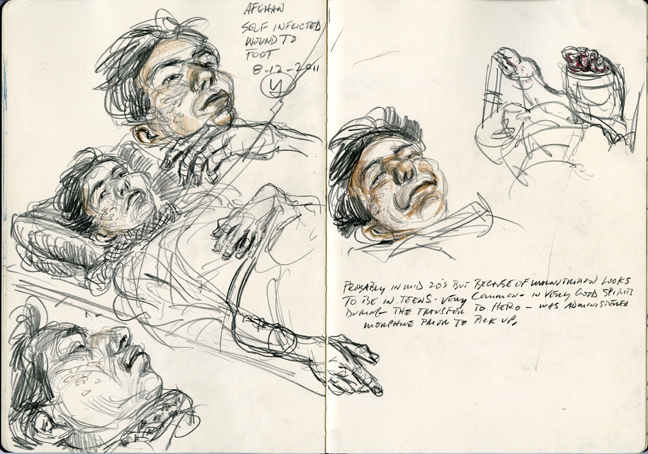

It was a unique privilege and honor to have had the opportunity to spend two weeks with the Alaskan 1-52nd Arctic Dustoff as well as with members of Alpha Company 7-101 from Ft. Campbell, Kentucky. I have a number of Facebook friends from the experience and keep in pretty close contact with several of them. Their sacrifices, bravery, and sense of duty are awe inspiring. Good people, all. I would do it again in a heartbeat. Only next time I would prefer to have someone else pick up the flight expense tab.